John Ammon Remembered (1888-1918)

John in his twenties John in his twenties(1908-13) with camera |

Also see: John Ammon Photo Gallery

Photo Galleries of World War 1: Northern France where John’s company fought and John died.

Introduction to a Short Life

How are people remembered after they die? Unless blessed or cursed with fame or infamy, the departed are usually recalled in family memories and in the recollections of friends for a while until the last ‘I knew him’ is buried. Silence and forgetting move in like the afternoon fog. Who of us recalls our great grandparents even if they lived into their eighties? And what about the many countless folks who die without offspring or without any important artifact of their ‘fourscore’ years of walking the earth?

And what about those who die young and virtually unnamed in the nightmare of warfare?

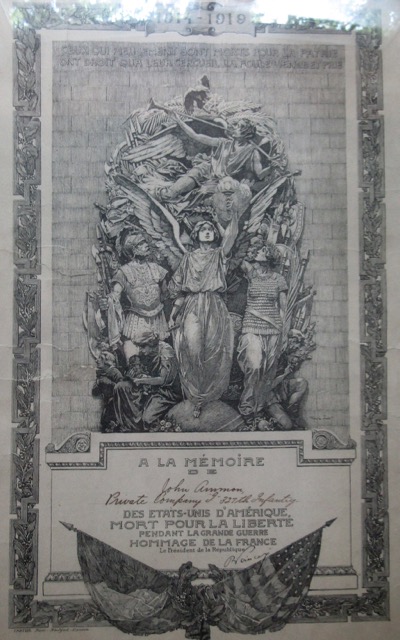

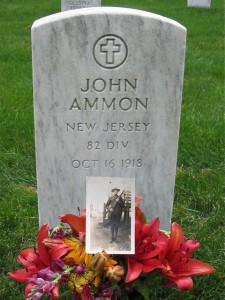

The brother of our grandfather Francis–Uncle John’ Ammon (born June 11, 1888)–as he is known, was neither a rebel nor a rich man, and was not well known. He was killed in 1918 in France as the First World War was within three weeks of the armistice on 11 November 1918 . He was 30, not married and not a father. Yet he didn’t die wholly anonymous. Instead of children or fortune he left a modest paper trail of his life in the form of photographs he took before the war as well as postcards and letters he wrote during his army time up to within a month of his demise.

Eighty-six years later, in the summer of 2004, his grandnephews Albert Fiacre and Richard Ammon cobbled together this memoir of John from the artifacts he left behind–his words and images–and from family stories.  They are presented here in a narrative as a memorial to a young man cut short in life, to a ‘hero’ who gave his life without complaint to preserve the freedom his descendants enjoy. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. I have visited there twice in my life. (photo right, 2014)

They are presented here in a narrative as a memorial to a young man cut short in life, to a ‘hero’ who gave his life without complaint to preserve the freedom his descendants enjoy. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. I have visited there twice in my life. (photo right, 2014)

John’s Early Life

Uncle John was grandpa Francis’ only brother; there were also four sisters, all born to Frederick Ammon (b. October 24, 1863) and Fanny Studer (b. 1859) who left their Swiss villages and shipped out to America. She was a Catholic from a French-speaking area and he from a Protestant Swiss-German-speaking area near the Capitol city Berne, from a town called Herzogenbuchsee. We have no idea how they met, but family rumor has it that neither of their families was pleased with their match. Perhaps this is one of the reasons they left home. (Francis commented much later that had his mother lived, the children would have been brought up as Catholics.)

They were unmarried at the time of their arrival (June 18, 1883 on board the ship Normandie) at the Castle Clinton immigration center in New York City. The original passenger log has them listed separately and with different last names: Frederick Ammon and Verina Studer (known as Fanny). How or why they made their way to Pennsylvania is not known, nor is the town, but they were apparently married there and Fanny became pregnant with their first-born Mary (Mame) in August of the next year and was delivered in April 1885. The subsequent different birthplaces of their children, first in Pennsylvania then New Jersey (Francis in Beach Glenn; John in Hibernia; Blanche in Rockaway) indicate the itinerant couple changed residency several times, perhaps as a result of Frederick’s work on farms or in carpentry; he followed wherever work was offered and eventually settled in the Succasunna-Rockaway area of New Jersey where apparently there was enough steady work, at least for a while. (Photo: Frederick about 1903, forty years old)

‘Settled’ is perhaps too suggestive of comfort. Frederick was obviously a low-wage manual worker. There is no word that they ever owned a house. As tenants, ‘home’ was usually felt as temporary. Neither he nor Fanny could speak much English at first; later they spoke with heavy French and Swiss-German accents making communication awkward. Friendships were probably not intimate beacuse of limited vocabulary. The hardships of inconsistent work and income must have added to the mental and physical demands of feeding and clothing their ever-increasing offspring. Within nine years of their arrival they had given birth to six children. It had to have been an energetic, noisy and tense household.

Whatever fragile sense of security the family had was shattered when Fanny died suddenly (some say willfully) from poisoning October 21, 1892, aged 33 , two months after the birth of their last child. Probably within days or a weeks, the hapless Frederick had little choice but to put his kids into the Morris County Children’s Home in Parsippany, NJ, not far away but still away from home and away from ma and pa. (John refers to his father in one letter as “Pa”.)

This put the infant Grace (2 months old), the infant Ethel (1 year, 7 months), Blanche (2 years, 2 months), John (4 years, 4 months), Francis (5 years, 8 months) and Mame (7 years, 6 months) in the care of strangers and, very likely, under the occasional eye of their bewildered and distraught father who remained in the area. We assume he continued to put his manual skills to work; he was only 29 (born October 24, 1863). He never remarried. (Whether he tried to reconstitute his family with a new wife is not known, but with several kids in tow, there were probably not many potential brides.)

Sadly, within the six years between 1892 an 1898 half of the Ammon children would be gone from the family. In the apparently aimless 25 years after Fanny died, 1892 to his death in 1917, Frederick made at least two trips back to Switzerland, each time returning to New Jersey. It is reported—vaguely in the recollections of Grace Ammon Bowman (born 1917)—that baby Grace died (possibly around the age of five) during or after one of these voyages with her father back to Switzerland. We suppose he hoped the baby could be raised by his family in his or Fanny’s hometown. But given the disturbed circumstances of their original departure, Frederick may have not have been met with open arms in either place. Offending religious tradition was not easily forgiven.

Another daughter, Ethel, second youngest, apparently died before the age of ten of unknown causes. (We assume she was living in the children’s home at that time.) Indeed almost everything about her is unknown as there is no ‘story’ or records about her. There are, however, two identical early photos of her in which she appears about 18 months old. One picture was found in a Swiss cousin’s (Hans,1992) album with a birth date of March 8, 1891. Evidently Frederick had sent this photo of little Ethel to his mother Elizabeth (1839-1904) and five siblings in Herzogenbuchsee. (His father had died in 1878.) An identical photo comes from Francis’ album with his hand-written words “Sister Ethel”.

A more cheerful fate awaited another of the Ammon sisters, Blanche. She was legally adopted by a family in Westboro, MA. It’s unfortunate but not too puzzling why Frederick consented to this distressful action; he understood that family life offered more opportunities for a child than an orphanage and he saw, after several years, no prospect of regrouping his own family. It could not have been an easy decision for him. This was about 1898 and by now baby Grace and little Ethel had died, so the loss of another sister had to have been very tearful for John (about 10), Francis (11 or 12) and Mame (about 13)–and, of course, for Blanche as well. She was only about seven and would have bonded strongly with her siblings.

Fortunately Blanche’s adoptive parents, the Gilmores, turned out to be loving toward Blanche and educated her well, including the New England Conservatory of Music. She became a violinist and kept in occasional touch by mail with Francis. She died prematurely in 1927 at the age of 37 of unknown causes. After her death, Francis and Cora went to Westboro and brought home “piles of music and Blanche’s violin which was given to Roger–your dad”, wrote Doris Ammon Strine (born 1914) in a memoir to Richard Ammon in 1984.

By 1898 the family had very much changed. Mame and Francis and probably John were no longer in the Children’s Home. Blanche was adopted out and the two babies were deceased. During these difficult years it might be suggested that Frederick slipped slowly into the mode of a sullen man who felt he had failed his family both in Switzerland and America, as well as himself. There are family comments that he was a ‘difficult’ man who did not take good care of himself, but possibly he was a broken man with little joy in his heart. After a manual worker’s life as farm hand, carpenter, horse handler (according to the 1900 census), school custodian and ore wagon wagon driver (1910 census) he died of pneumonia on January 13, 1917, aged 53–about 6 months before John entered the army.

There is a record that indicates Frederick for a while lived in a boarding house (in Succasunna or Dover?) managed by Mame (after her divorce sometime in the early 19-teens). Reflecting ‘hard feelings’ toward Frederick for putting the children in an orphanage, son Francis never marked his father’s grave in Succasunna, NJ with a headstone. (This was done in 2003 by Albert and Richard.)

As for John, we have no record about his feelings for his father, good or bad. He wrote a single comment to Francis, almost in passing, in one of his letters making reference to his father’s demise: “How are you progressing with the estate?”

There are no detailed records of the schooling, demeanor, activities, health, quality (or lack) of care or skills of the children, Mame, Francis and John or Blanche while they resided at the Chidlren’s Home. It’s likely their pre-adolescent childhood events were similar to Francis’ (whose harsh early life is somewhat known from anecdotes and comments told in our family) as they were all within five years of each other. Raised in the Children’s Home from the age of seven, five and three-and-a-half, and two, respectively, they received shelter, food and some primary education until each was old enough to be hired out as a farm hand or domestic help–or adopted. (Were they paid? Who received the money? One family story holds that Frederick received the money.)

In her memoir Doris Ammon Strine fills in about John: “He was not adopted but he apparently was taken from the home by a Newark, N.J. family, given good schooling and the necessities for good living.” It’s unknown what age John ‘was taken’ or if he had been farmed out earlier, as Francis had been (“dressed in thread-bare clothes in freezing weather…”). It’s likely John at least worked occasionally with his big brother who kept a watchful eye on him—although not little for long. John, in his teens (1901-1908), became much taller than Francis and eventually grew to 6’4”, towering over Francis at 5’10”.

John’s level of his education is suggested in his numerous letters which reveal clear and practiced cursive writing and good spelling for the most part, including well-composed words such as ‘furlough’, ‘neighborhood’, ‘scaffold’ or ‘expression’. But the flaws in his learning are also reflected in numerous misspellings of common words such as ‘quiet’ (for quite), ‘usto’ (used to) or ‘baloon’.

So it appears that around the age of ten to fourteen Mame’s, Francis’ and John’s lives began to diverge from each other. Francis and Mame remained in the rural countryside (perhaps Frederick found work for them with him on occasion) while John went to live in the city. It’s not hard to discern the effect of these early events by reflecting on their later lives: Francis and Mary (until she married at 18) continued semi-skilled manual farm/carpentry/domestic work in the pastoral Succasunna-Hibernia-Dover areas of New Jersey Francis worked briefly in Brooklyn, but soon returned to rural New Jersey. It’s reported that both of them lived, on and off, with different families in the area of the Children’s Home.

Regarding this, Doris wrote, “Mary and Francis were sent to foster homes to ‘earn their keep’, as the saying goes. Francis left on March 3, 1898 (he was just 11 years old) and went with a farm family near Morristown, N.J. I have the parting gift which the Home gave him: ‘The House of Seven Gables’ by Nathaniel Hawthorne. They also gave him a Bible (also in my possession) dated 1898, with a special psalm written in the flyleaf. All this is most sentimental to me…his sister Mary had a similar early life and at one time was living with a family only a mile or so from where her brother was living.”

John, understandably, became more urbane, more commercial and business-minded. He seems to have adapted well to life in the big city of Newark and he eventually opened his own jewelry business in his mid-twenties, around 1914-17. (Doris wrote the business was “a confectionary store”.) The 1910 census (John 21 years old) has him listed as a “street railway conductor”, a coat-and-tie job which paid reasonably well in those days. His later letters portray him as frugal and modest which may have allowed him to save up enough capital to open his business (with a partner).

Yet, despite their emerging different lifestyles, there was a comfortable and loving camaraderie between the brothers and their sister. Mame was ‘married off’ in 1903 at the youthful age of 18 (John was 14 and Francis was 16) so her focus became her husband, her children–the first within a year–and, soon, the problems of her husband’s ‘weakness’ for alcohol. Francis and John probably saw each other with some regularity as there was train service between Newark and Dover. John mentions in one of his letters that Mame might pick him up at the station. There is clear evidence that John also very much appreciated Francis new wife Cora.

John in his late teens 1903-08 John in his late teens 1903-08 |

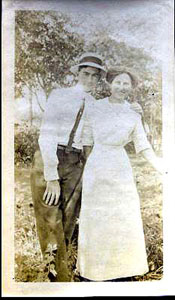

As for Francis’ wedding to Cora Van Tassel Smith on June 23, 1910 it’s unlikely that John attended as they were married in ‘far-off” Mehoopany, Pennsylvania. Francis was 23 and Cora 25. (They had met in New Jersey where Cora lived with a cousin during her first year of teaching.) A photograph of the rustic wedding party shows only the young couple and her parents, Anson and Mary Smith. After Cora came to New Jersey she soon exchanged he career for the profession of motherhood.

As early as 1911–when John was 22–Francis and Cora had their first child, Ethel, who also attracted John to their home. He loved his nieces and nephews as they came along. By this time, Mame had two sons, Bill (1904) and Edward (1908). As part of their shared friendship, Francis and John both bought cameras in the early 19-teens and, according to Doris (the third born to Cora and Francis), enjoyed taking photos together.

John left behind an extant photo album of about thirty images prior to his enlistment. The pictures are not artistic in the sense that he staged or posed his subjects or that he tried to suggest a story or point of view. Rather his snapshots appear as tokens of curiosity and appreciation of the common moment–friends lounging on a picnic blanket; a ship in a harbor; boyfriends with their girlfriends or John himself with girlfriends. There appears to be a simple and easy theme here, as uncomplicated and straight forward as the photographer himself. It’s curious, however, that there are no images of his family (including his father) in the album–although there may have been other albums.

His adult appearance was youthful with smooth facial features, perhaps like his mother, with long dark eyebrows and a soft mouth. “He was very handsome,” wrote Doris. And perhaps also like his mother, of a sensitive and artistic nature in love with life. He grew to a height of 6’4’, as mentioned before, and had a thick shock of wavy hair that, in some photos, appeared a bit out of control.

His affection and attachment to his brother and sister is evident, in retrospect, in the several letters he wrote which virtually always asked or told about news of their health and the children. One letter, from the war front urged Francis to write as soon as he could since a delay of even one day could mean two weeks delay in John’s receiving it. He was very eager to hear from home. He doted on the children before going off to war. By the time he left for Europe in summer 1918 Francis and Cora had four of their eventual six children: Ethel was seven; Roger (father of Richard Ammon) was six; Doris was four and Grace was about one. Mame’s son Bill was fourteen and Eddie was ten. For a while, it seemed the Ammon family had been remade.

Entering into History: Letters from John to his Brother Francis 1917-18

Not much information other than this might have been known about John were it not for his being conscripted into the army in 1917 at the age of 29. This significant turn of fate began a modest stream of letters and cards to his family from his camp assignments and from the front lines in France in which he described the great events that changed his life.

In the ten extant letters that have been preserved, there is no ponderous wonderings about the meaning or sense of life, no outbursts of frustration, no railing against army life, no political positioning. There is no anguish and no complaining. Nor is there artistic imagining or colored narrative. Instead he describes his daily life with a calm objectivity, almost as a reporter of passing events. Reading these messages suggests he had a steady even nature that sincerely and thoughtfully engaged him, in a manner of fairness, in whatever and wherever he happened to be.

John on right with friends about 1908-13 John on right with friends about 1908-13 |

Whether it was reporting about friends at home, dealing with his slippery business partner, fending off buddies in his barracks trying to grub cigarettes or cookies, his efficient attention to duties in the mess hall, his determination to be an excellent rifleman or his worry to be equal-handed in his will, he expressed clear-minded and measured reactions.

Later, in the harrowing combat conditions—gas warfare, ducking artillery shells, tasteless rations, the maiming and death of buddies, the persecution of weather, digging trenches in view of the enemy, on guard for attack–John’s messages are descriptive not indulgent, straight forward and without introspection or angst. His narratives are unembellished and the handwriting tidy. Even in he shadows of war he had the presence of mind to write about the French farmers cutting their harvest or how rich the crimson clover was.

The letters can be divided into two distinct time segments; the first dating from his induction into the army around July 1917 up to his departure for the war in May 1918. There are seven letters from this time in which he describes training and camp life.

After shipping overseas there are, disappointingly, only three letters that survive. These letters narrate the dramatic, disturbing and traumatic final six months of John’s life. From a young farm boy with a delight in photography who grew to become a business man and a doting uncle, John was pushed into the role of patriotic warrior fearlessly ready to use his rapid-fire gun on the “Huns” day or night.

First months in the Army: Camp Dix, NJ

John registered for the draft on June 5, 1917 as recorded on his draft card of that date. He was 28 years old, six days short of his 29th birthday on June 11, and living in Newark, NJ. As mentioned before, he 1910 census had his profession listed as a street railway conductor, a respectable job of some responsibility. Around 1912 he met a man named Frank Smith with whom he ventured into the jewelry business in Newark three or four years later. When John entered the army he turned the “booming’ business over to Frank.

There are no written documents that testify about his pre-army adult life, friendships or adventures. There are photos from this period that show him with friends and girlfriends picnicking or rowing boats, all dressed rather politely in coat and tie suggesting a preference for good grooming and fashionable dress.

It appears that John entered the army in the summer of 1917 and was assigned to Camp Dix, in NJ. He doesn’t write the date on the first surviving letter but there is no mention of cold weather when he tells, “In drilling we have to kneel, roll around on the ground and go through strenuous drilling. Eight hours drilling make up our field duty and about one hour is consumed for washing clothes and cleaning up around the barracks.”

In subsequent letters John commonly observes the weather if it’s “dandy’ or harsh so the lack of comment here suggests a mild time of year for his army induction. (He also mentions in the next sentence, in a rare judgmental way, that , “I am amongst the biggest bunch of bums I ever came in contact with…half of them are from Hoboken….such a nosey bunch. If you get a package lots of them figure you have eats and hang around for a share.”)

Apparently the troops were not issued uniforms at first so they used their own clothes at Camp Dix until they received uniforms a while later. As mentioned , he tended to be fastidious in appearance, as suggested before in his leisure time photos. So when he eventually tried on his uniform he was not pleased: “I got it today and believe me it looks punk. Remember Pa’s iron shoes. Mine are worse. They are spiked on the heels and souls and weigh 12 lbs. Size 9 1/2. If I ever enter your house with them on shower me with a ton of coal. If you don’t your hard wood floor will be scraped.”

Camp Dix was still under construction when he arrived as he described, “there was about 7000 carpenters and plumbers working here for a while. They get 60 cents per hour and half pay extra for Saturday PM and Sunday. 10 hours daily. In the Long Island camp I heard they got 67 1/2 and double time for overtime.”

His daily routine started early: “I am in jail now. Have to be in at 9:30 and in bed at 10 and up at 5:45. We start to drill at 7:00. Almost like the farm.” This comment about the farm is one of the very few references John made to his past as a younger person. It infers he indeed had some farm-hand experience, porbably as a child, and this wording also suggests he and Francis had worked side by side at least once.

Transfer to Georgia: Camp Gordon

Sometime around late October or early November 1917 John’s group–I Company, 327th Infantry–was moved by train south to Georgia to Camp Gordon, 12 miles from Atlanta, so they could work outdoors all winter. On the trip south he noted that two men deserted in Baltimore and two more in Virginia. He didn’t think they would get far: “Uncle Sam has our fingerprints and body marks.” His company remained at this camp throughout the winter and spring of 1917-18 until they shipped overseas.

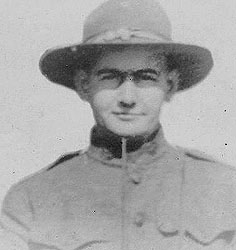

John in uniform 1917 John in uniform 1917 |

Curiously, this was not John’s first trip to the southern states. In his first letter from Georgia, he describes how the price of cotton has gone up drastically since his previous visit: “When I was through this section in 1914 cotton was selling for seven cents a lb. Now it is bringing 30 cents. Remember the Buy the Bale year. That was the time. Those who bought a bale paid $50.00 for it. Now it sells for $190.00 a bale.

At Camp Gordon the training routine was different than basic training at Camp Dix. “We do not drill as hard as we did at Camp Dix. The program is different. We go out to the grounds at 7:15. Have physical exercises for half an hour. Then we run for five minutes. Then rest for five minutes. Then each Co has to assemble together and sing for 15 minutes. Talk about harmony. I hear better music in the dinning room when some of the waps are eating soup than some fellows can produce on the field.”

Knowing full well that brother Francis prided himself on his ‘basso profundo’ singing voice in the church choir, John playfully tells him, “Bet you are grinning now and telling Cora that perhaps my harmony is in the dinning room class.”

In addition to the attempt at singing I-Company had a ‘yell’ which John described as “123-12-1234567-327, Hurrah for I-Company. That’s our yell and we get it out like a bunch of college boys. But when you give the crowd the once over you wonder what city scavenger wagon they worked on.”

John’s disdain for certain ‘under class’ people is evident here and in other references such as the above ‘waps’ who cannot sing, or the “biggest bunch of bums” in his company, or the “nosey bunch” who want food from others’ packages. It’s hard to discern if he is serious or just playfully sarcastic toward them, although he later refers to “75% of the boys that have money roll dice and play poker—sometimes in the latrine after lights out. I am glad I don’t play either of the two games mentioned. They are sure loser’s (sp).”

These are the only critical comments he makes about others in his letters, aside from his hints at the implied foolishness of those who volunteer for overseas duty or cannot figure out how to avoid arduous grunt work in the camp. (Despite John’s coming from a very blue collar family it’s evident he developed a ‘higher’ standard of living. No doubt it was the influence of the the family who took him from the Children’s Home to live in Newark as a pre- or young teen.)

On one such occasion he craftily eluded “grubbing stumps’ by telling his corporal he need to go get an axe to help clear tree roots: “I dug for about five minutes, got tired, droped (sp) my pick and said to the corporal “We need an axe to cut the roots with.’ He told me to get one and he’s been looking for it ever since.”

Post card sent home by John showing morning wash time Post card sent home by John showing morning wash timeat Camp Gordon, Georgia 1917. |

John also managed to shirk other tedious work when he could: “Every morning we have to clean up the grounds, latrines, barracks, stoves, and etc, but I am not around.” A few lines later he tells how he avoided an afternoon hike by going to the dentist and returning to the barracks instead. But he was clearly not pleased with the quality of dental work on the camp: “no more army dentist to practise (sp) on me. Some of them are better fitted to put cement on a sidewalk instead of teeth.”

However, John didn’t seem to mind purposeful drilling and training since he was apparently strong as well as standing 6’4” and did not “have one sick day since comming (sp) to camp.” Early on, he had written Francis from Camp Dix, “I expect to look better physically and will try to be better personally.” Not an immodest comment from this capable and competent young man.

At Camp Gordon, his company usually went on training walks: “Talking about duck I am beginning to think I am more of one than a soldier. On Fridays we walk 15 miles in four hours…speaking of the Friday AM hike a week ago, the Boys began to drop out by the dozens on account of the stiff pace. One fellow died. With heavy shoes and nine pound gun it is rather hard. My tongue was hanging out when I got back, I stood it well last Friday.” In the afternoons except Friday and Saturday, “we go on an eight miles walk and go in some corn fields and through some woods with a gun on our sholders (sp), taking up a drill call scrimishers. That is pretending to attack the enemy.”

After several months at Camp Gordon, early spring of 1918, John explains that he nearly had a full compliment of equipment. “We have almost our full equipment now, and we look like real soldiers as we trod along the road, with our blankets, clothing, toilet supplies, ration cans, emergency equipment and canteen bottles. Our entire load will be in the neighborhood of sixty pounds. I can see the small fellows stooping over under the heavy load but I expect to carry mine with ease.” He doesn’t say if this includes a gun and bayonet which would have been another 14 pounds.

Occasionally, John reports, there is a mass parade. “On Saturday morning 40,000 of us assembled on a 40 acre field and parade before the General. We have about twenty full piece bands and one of the twenty is playing continuously. We have quiet (sp) a few hundred visitors to watch us parade, and it is quiet (sp) impressive. The two Saturdays I was in the parade here a mule balked each time. It was comical and we all had to laugh. The mule was being led.”

For better quality music, John tells of having a record player (gramophone?) in the squad room, “and we chip in each month to get a new record.”

Assistant Mess-Hall ‘Sergent’

At some point John was put in charge of a mess hall (one of them) for the camp, overseeing the daily assignees to be sure they completed their tasks of cleaning up properly. There is a hint here, one of several throughout his letters, that he seemed inclined to be a natural leader and was easy with taking charge, yet without forcing himself on others. His unusual height certainly lent itself to this tendency. (See the incident below regarding the Company photograph session for another suggestion of his influence.)

Inspection Time, Camp Gordon, Georgia Inspection Time, Camp Gordon, Georgia |

From Camp Gordon in early spring 1918 (“the peach trees have been in blossom since the first, also the apple trees are in bloom with the leaves appearing”) he sent a photograph (now missing) to Francis and sister Mame; “The one picture is of my mess-sargent (sp) on the right and a cook on the left. Both fine fellows. By rights I am supposed to be called assistent (sp) mess-sargent (sp), instead of mess-hall orderly.” Later, he wondered, “Don’t know how this job will effect me in Europe. I suppose the mess hall will be out in the open.” From reading his last letters from France it appears he was not assigned to mess hall duties overseas as he was “ducking shells” and posting watch at night in the trenches.)

Private John Ammon may have been the only army recruit to admit liking the camp food. “Our eatables are quiet (sp) good here, lots of variety and usually plenty to each. The quality is not very fancy. The captain says it will be better soon. I am quiet (sp) contend (sp) and feel good each day.” In one letter from Camp Gordon John relishes the idea (or rumor) that “we have a good duck dinner comming (sp) for Thanksgiving.” But this doesn’t stop him from preferring to “go to Atlanta which is twelve miles from here, buy my own dinner and take in a show”–another clue that his interests were very different from rolling dice or grubbing food from others.

Regarding photos of himself, John revealed his vanity about his once-long and thick wavy hair: “Did you get the other Post Card pictures of me? I would like to get a large one taken, but due to the order permitting us to wear our hair only 1/2 inch long I know it wont (sp) look good, so why spend good money for poor work.”

As a result of his mess-hall assignment, “I get about five off hours to myself each day while the other Boys are putting in eight strenuous hours of drill daily. Carrying an 11 lb rifle with an 18 inch bayonet attached weighing about 3 lbs. They come by the barracks at nine from dummy bayonet practice and sometimes they look to be all in. These dummies are made of sticks about the size of a cane, and hung on a scaffold, shaped like a sheaf of wheat. How the Boys do jab their bayonets in. We have English officers training us in the bayonet exercise. They seem to have the goods, that is why they are here, but they strike us as a joke. We have a few French men around. They are fine built fellows and they appeal to us very much. They teach us how to dig trenches, and use the machine gun.”

Post card sent home by John showing training in trench digging, Camp Gordon,. Georgia 1917. Post card sent home by John showing training in trench digging, Camp Gordon,. Georgia 1917. |

Aiming for Sharpshooter

Shooting appealed to John. From the first he looked forward to becoming a sharpshooter and he came very close to that goal. From his early days at Camp Gordon he wrote: “Our regiment of about 2000 go to the rifle range Monday for a whole week. I am anxious to go often, as I want to make some good shooting records and come out around the top.”

In his longest letter home, eleven handwritten pages in very clear script and few spelling errors, February 1918, ‘assistant mess-sargent’ Ammon felt confident about his abilities on the shooting range. “Our company of 250 men took a nine mile hike to the rifle range. Our first shooting was called the trial, and I was twelfth highest, our second shooting was the test and we only had about 25 who qualified from the trial. Out of the 25 I came out second best, being beaten by one point, and being tied with the best shooters at 300 yards. We shot at 100-200 and 300 yards in a prone position. I qualified for a marksman and was one point short of being a sharpshooter. In peace times soldiers get bars for good rifle work, but I have not been able to learn weather (sp) we will get the marksman’s bar or not.”

As a result of this confidence behind his weapon he wrote Francis that, with the rumors swirling around camp about imminent deployment to France, “I for one am ready, and when I tell you of my good work on the rifle range you can readily understand why Johnny is ready.”

Post card sent home by John. showing patriotic zeal against the ‘Huns’. Post card sent home by John. showing patriotic zeal against the ‘Huns’. |

Such patriotic assurance was not unusual among young inexperienced American recruits in 1918. Once the U.S. was committed to the war, countless innocent soldiers and sailors felt called to the mission to save the world from danger by defeating the enemy “Huns”, as John called the Germans. John’s sense of pride and purpose in the call was also evident when he wrote, in December 1917, “It is getting time to line up for retreat and hear our 30 piece band play the S.S.B. (Star Spangled Banner) while we stand at present arm’s (sp). Don’t think I will ever get tired of hearing it.” He also loved to hear the blowing of taps at the end of the day, “the sweetest music of all bugle calls.”

Contributing to the troops’ zeal were ongoing lectures about the war and the rightness of the American and Allied cause. After one talk, John wrote to Francis, “Just heard a French speaker to night (sp) and he tells us Trotsky of Russia is a German and his other name is Boveleski or something like that.”

Lighter Moments for the Troops

But there were many lighter moments at camp as well and life was not constant ardor and labor and propaganda. The YMCA organization was actively engaged with military personnel during this time. It created recreation centers on or close to the camps so that soldiers had a place to go for recreation, socializing and entertainment. Both in New Jersey and Georgia John reports pleasant times at the ‘Y’.

All of John’s letters are written on stationery provided by the Y with their triangle logo at the top and their slogan ‘with the colors’ printed on each page. Also across the top, in Camp Dix, New Jersey, were the headings ‘War Work Council, Army and Navy Young Men’s Christian Association’.

“These Y.M.C.A. are fine places of recreation. Last night we had a small show got up by the Boys of one of the Co’s. Tonight we have a minister lectureing (sp) and a choir of about 20 singing. We enjoy everything that goes on.” On another occasion he wrote: “ I just came from the Y.M.C.A. tonight after being entertained by a few young ladies who sang and recited. The closing song was ‘Over There’ and by the loud noise, one would think we are anxious to go ‘over there’.”

This was written in the early spring of 1918 so the hint of uncertainty in his words reflected his early ambivalence about shipping over to Europe. But as John became more proficient with his rifle, his self-confidence increased to the point of ‘Johnny is ready’, as we have read.

For sports, John mention twice that he joined in his I-Company baseball games: “At baseball I pitch occasionally.” This evidently level-headed man also reveals himself as playful and ready for a joke or prank. He elaborates about some trickery his company played on other companies during a photo session one afternoon in front of the YMCA. His 327 Infantry I-Company made a sign with their name and held it up in the first picture. Since they were the only company out of several with a sign the others protested and made them put it down for the second shot. It so happened that the camera was a revolving type that took one portion of the wide-angle troops at a time so John’s company put the sign back up just before the camera turned to them. “The machine has passed the Boys on the other end, so they are mad and hollering at us to put it down, that is why we are laughing. The other companys (sp) refused to buy the picture so the photographer told us he would have to cut out the line I-Company.”

He finishes up his comments: “Each company tries to slip something over on the other. We are among the leaders. We win very often.” Given the elaborate description that John lavishes on this prank, it would not be surprising if John were indeed one of the mischievous ringleaders of the folly. He also includes a P.S in this letter with one of only two slight references to religious matters: “I forgot to say there are more fellows in the picture than belong in the bible (sp) class.” This either suggests he attended that class or he may be commenting on the lack of religious concern in his peers.

Getting Close to Shipping Out

A constant and mysterious concern for all the troops was if, when and where they would ship out to Europe. As early as December 1917, John wrote to Francis: “Our camp is just as great for rumors as ‘no doubt’ your shop is. We had been here only a short time when someone started a rumor that we were going to Texas. The next rumor was we were going over to France shortly, for if we remained at camp longer the new drafted men would have no place to drill. Our General left for Washington D.C. a short time and from there he was reported on the way to France to prepare for us.” There was also gossip floating around that had them going to Hoboken, NJ or Cuba.

. “Johnny is ready,” wrote John in spring 1918. . “Johnny is ready,” wrote John in spring 1918. |

John’s last extant domestic letter is dated April 4, 1918 in which he describes various signs of imminent departure for France. “One of the boys from our I-Company is working over in the officers’ quarters painting their names on their blankets. So it looks as if some thing is going to happen… Our identification tags are being made out now. One goes around the neck and the other around the wrist. We were all issued a baby pick and shovel today. I believe they are for sanitary conditions on the battlefield…All of our clothing has been checked up, which is an indication of a near departure.

“I have confidence in being able to get home before I go over, from some northern camp. Of course this is all guess work.” (Earlier John had said the rumor was they would go to Camp Upton in upstate New York. This rumor turned out to be accurate. He wrote his will there–April 24, 1918–before they embarked from New York City (most likely).

Before I-Company left Camp Gordon in Georgia, John wrote about one of their most important defense training procedures, use of gas masks. World War I was notorious for its brutal means of warfare, not the least of which was the use of chemical weapons such as the highly toxic and deadly mustard gas. “I saw one company drilling with gas masks today. The gas <real gas?> would be thrown in a group and the Boys would slip on their masks which they carry over their shoulders like school books in a canvas case. Six seconds is the time they are supposed to get them on.”

Although John does not say he participated in this particular drill, all troops were trained in gas mask use. In a subsequent letter from France John described in harrowing detail how this training became a matter of life or death as his company came under a mustard gas assault (described below).

Personal Matters

Before we follow John to Europe, there are several other personal matters that he reveals in the seven letters he wrote between Spring 1917 and May 1918 during his time in the New Jersey and Georgia camps.

Self Revelation

Throughout these letters John, in his 29th year, removed far from his family, without his beloved camera, and separated from his business and friends, offers virtually no complaints about his radically changed living circumstance. Nor does he bemoan his Spartan life with emotional moans, grievances or grumbling about the unfairness or discomfort of his lot. Introspective reflection or self-doubt did not seem pressing or important to him. Being separated from his beloved family at Christmas 1917 was disappointing to him but he also wrote evenly, “Kindly extend my Christmas and New Years greeting to all. I feel that I will be quiet (sp) content here over the Holidays. Regards for the Children.”

In a subsequent message he mused optimistically: “Sometimes I think if I get out of the army safely I will settle down, I have a choice of four <girlfriends?> to select from, but perhaps if when I get out, I should get a position that takes me away considerably I will give up the idea.”

John with a girlfriend John with a girlfriend |

His attachment to others outside his family seems rather light, even regarding his most constant girlfriend ‘Net’–a bit surprising for a young man in his ‘prime’; there’s no hint of ‘passion’ or desire for her or anyone else. But, as he was writing to his brother, such concerns may not have been part of their arena of conversation.

Family

His family–brother Francis and wife Cora, sister Mame (now divorced) and their children, three nephews and three nieces—always remained close to his heart and in nearly every letter he asks how they are doing. He wrote to them and they to him with pictures. (Sadly, we do not have any of these letters, only three postcards with very short messages.) He wrote in one letter, “Got a letter from Marion on Good Friday. She says I should ask the Captain for a furlough for Easter. It is a good idea.”

He sent money ($5) to Francis and Mame at Christmas 1917 to buy the children gifts. Other times he wrote: “How glad I was to hear of Ethel’s (then seven) report in school. Something to be proud of.” Later, “How is all the family? How I am longing to see the kids ‘and all that’ again.” Also from Camp Gordon he wrote: “I wrote to Bill and Ed (sons of Mame) to cheer them up. I must write to Mame tomorrow.”

In the next letter, April 1918, John was very pleased: “The picture of the children was received in good shape. All the Boys thought they were three of the finest children they had ever saw, especially Doris who most everyone says is so cute. Many thanks. You have something to be proud of and each year you seem reaching the goal that you have aimed for, years back.”

Concern for His Brother Francis and Sister Mame

Mame, about 1910, aged 25. Mame, about 1910, aged 25. |

Mame (listed as a “servant” in the 1900 census) had married William Palmer (in the census, a “retail butcher”) when she was only 18 in 1903. Unfortunately Palmer had a drinking problem and doubtless became abusive to Mame, which must have been a serious worry for Francis and John. Her first son William Frederick Palmer was born May 12, 1904 (died November 27, 1993) and Edward Francis Palmer came along in April 4, 1908 (died March 1982). It is no small clue here how much affection she had for her father Frederick and brother Francis in that she gave her sons middle names after them. Over the years, she seems to have been the closest of the three children to Frederick.

Mame suffered through several years (10 or 12) with Palmer, probably for the sake of the children, and later divorced him sometime between 1910 and 1915. (She remarried in 1927 to a kinder Joseph Sauder.) As well as bearing two children she worked as a domestic housekeeper and practical nurse. As mentioned, after her divorce, she managed a boarding house in Succasunna or Dover where her father also lived for a time.

The strain of her worries took its toll on her health as she developed a ‘weak heart’. John’s ever-vigilant thoughts toward Mame are seen in a letter from Camp Upton in New York in which he tells Francis: “I have taken out $6000 insurance, and if I should fail to return it goes divided among the beneficiary I name <spelled ‘mane’>.” He goes on to list how the money should be divided among Francis’ and Mame’s families. Then he writes, “I had the policy made out in your (Francis’) name <again spelled ‘mane’>, the reason being, on account of Mame complaining of heart attacks and other severe troubles that attack her from time to time.”

At the time of this letter Mame was only 31 years old. We can only guess that her previous troubled marriage had taken a harsh toll on her, leading John to be apprehensive about her. In another letter dated April 24, 1918, very shortly before his departure for Europe, John wrote to Francis again about the terms of his will which gave more money <$3000 over time> to Mame than to Francis directly. (John divided the remaining $3000 among his nephews and nieces equally.) John was concerned that Francis should understand his reasons for these terms: “I trust you will not feel that I have slighted you, by giving Mame a much larger portion than you. Fairness has always been my policy and to treat all fair has caused me quiet (sp) a lot of worry and thought. You can readily understand Mame’s position and due to her misfortune and ill health I feel that the time will come when this tidy little sum will look good to her and be needed.” These are clearly the words of a devoted and sensitive brother.

Francis, possibly at Mame’s wedding about 1904. Francis, possibly at Mame’s wedding about 1904. |

As for Francis, in comparison to John’s relatively agreeable style and even-tempered nature Francis seemed to suffer the most, mentally, from their traumatic childhood of torn love, neglect and misuse as a child farm worker. Francis’ personal life is a separate story but from the exchange of letters between the brothers it appears they both wrote to each regularly, although Francis less so because of his work and family–and moods. Their correspondence covered personal, family, social and business affairs.

Unfortunately for us, John said in one letter: “I received a long letter from Mame the same day yours came, and as I burn each letter after writing <replying to> it, I cannot recall any important news she sent.” With the burning of his correspondence any c inspection of Francis or Mame in their own words is lost. However, some personal details about Francis can be gleaned from John’s concerned replies. “I have read over your letter and touched on all the subjects of importance”, indicating John was a careful reader and attentive responder.

There seemed to be a shared confidence between the two brothers. In one letter John described personal gossip about some mutual friends and neighbors and finished up with “Kindly keep your neighbor’s news confidential. You are the only one I will tell.” Later, John also entrusted his financial and legal affairs to Francis after being betrayed by his business partner. (More of this below.)

John’s letters as well as family anecdotes reveal that Francis, unlike John, was ‘ unsettled’ by nature (or nurture?). John was less than two years younger than Francis yet he expressed a big brotherly concern in a couple of letters home. “Regret to learn you are run down from so much hard work. Remember you are a young man yet “and while I realize it is important for you to keep going” (quote marks are John’s and probably refer to Francis’ own words) try to conserve yourself for the hardships that the future may force upon you. I believe in making hay while the sun shines but I want to get a little good out of life as I go along. Life is to (sp) short and uncertain.” This is the only reference John makes to his own view of life. In closing this letter of February 1918 from Camp Gordon John tells Francis: “I must close hoping to hear form your when you do not feel to (sp) tired to write.”

Francis’ feeling run down at this time may well have had to do with a major project: in 1917-18 he used his considerable skills to build a large house in Succasunna for his growing family now numbering four children (Ethel, Roger, Doris, Grace). He had gained a steady (1914-52) job as maintenance foreman with the Hercules Powder Company in nearby Kenvil, NJ. to which he rode his bicycle each day except, as John commented, in deep snow after the blizzard of 1917.

Francis and Cora’s house, built in 1917-18. Francis and Cora’s house, built in 1917-18.Pictured here about 1930. |

The construction of this house, one of the largest in the area, was not just a shelter for his family, but it surely served as a visible and potent symbol of an ‘established’ family–the “goal” that John refers to in one letter to Francis. (“You have something to be proud of and each year you seem reaching the goal that you have aimed for, years back.”) Out of the chaos and disintegration of his early family life, Francis had ‘reconstructed’ the Ammon household, outwardly at least…if only it had been that easy. (Many years later, in hushed converstions, the daughters of Francis and Cora revealed the delights but also the tribulations behind closed doors of their childhood. But that too is also another story.)

A further bit about Francis comes from a poignant letter he wrote to John, sent four days before he received the final news of John’s death. (The letter was subsequently returned to Francis nearly a month later with the word ‘deceased’ stamped under Private John Ammon’s name.) In this letter Francis writes about the severe influenza epidemic of 1918 that killed 100,000 people but affected his family only by the closing the local schools: “There was no school for six weeks during Oct. and Nov. so the kids had a good time all fall.” However, Francis wrote, a neighbor of theirs, ‘Juice’ Meeker, “died while in training camp of influenza.” About himself, Francis closes the letter with, “Have a powder headache so think I will stop now. Can you get a chance to see the aunts <in Switzerland> while over there? Good By and Good luck. Yours, Francis Ammon.” It is known that Francis suffered from headaches as well as mood swings. Afterwards, the shock of John’s death no doubt exacerbated Francis’ uneasy disposition. Like father like son.

Friends

John appeared to have been gregarious and affable in his friendships. He received letters and gifts such as clothing, food and cigars on a regular basis. One of his most frequent correspondents appears to have been a Miss ‘Net’ (short for Antoinette?) Reeves with whom John seemed comfortable and warm. She wrote to him often. “Got a long letter from Net asking me if I need any knit goods. So far I have been very comfortable. She wanted to know what kind of stuff they gave us to eat. I usto (sp) call it junk, but of late it has been very satisfactory.”

Later in the same letter John writes: “Net <a teacher> says they may not have school for Jan. or Feb (1918) and if she is home the cat is liable to run one way and the dog the other”, referring to the disagreeableness between Net and her mother. The closing of the schools was possibly due to the shortage of coal for the furnaces and/or the threat of infection from influenza that plagued America at that time. Francis also mentioned the shortage and said the government encouraged wood burning instead, thus saving coal for crucial war materiel factories

Two months later, from Camp Gordon in Georgia, John wrote: “Net also sent me a prize box of 10 cent cigars, and I gave her a nice cameo ring. She said she had wanted her mother to get her one for years. Guess she was well pleased with the ring. I have not smoked for over two weeks and I hope I can continue to get along without them. I have a few on the shelve (sp) left, sent to me by a friend from Newark, but they do not annoy me. I just leave them there to see if they can get my nannie. I suppose if they were around you, you would touch a match to them. How is your old corn cob pipe getting along anyway?”

Other friends are named or briefly mentioned throughout his letters. A fellow named Ray was put in military class 2. “He was in class 1-A and they made quiet (sp) a stir because he did not try for exemption. Maybe he thinks one war <at home?> at a time is enough.”

Another seemingly devoted friend, Irene Harris of Glen Ridge, NJ, is known to us from her extant two-letter

John with more friends John with more friends |

correspondence with “Mrs Ammon” in December 1918 and April 1919 after she learned of John’s death. In the first letter she writes, “I’ve known and corresponded with John for over five years. And during those years I’ve enjoyed his letters while he was away and considered him one of the finest fellows that I’ve ever known.” She expresses her heartfelt sympathy mistakenly thinking Francis’ wife Cora was John’s mother. She also asks for details of John’s last days, what battle he was in and where he fell, hoping perhaps the published list of war dead was mistaken.

We assume Francis (or possible Cora, as Irene’s next letter still addresses Mrs. Ammon) responded to Irene saying they knew almost nothing of John’s particulars. In April 1919 Irene wrote back saying she had upon request received details about John’s last stand from his Captain. “I think its (sp) just wonderful to think that he would take the time to tell all those details and I am so glad to know them as up to now I had thought that probably they (sp) might have been a case of mistaken identity. But the letter proves that John was doing his duty to his country and fellow men until the time of his death. And also I think it’s a great consolation to know he did not suffer for hours like some less fortunate boys.” This is the only detail we have about John’s moment of death, that it was sudden. Unfortunately, the letter that Irene copied from John’s captain describing the circumstances of John last moments is missing.

The Troubled Exception

John’s even-tempered personality and his strong sense of fairness seemed to have netted him good friends in return who sent him best wishes for a safe outcome to his military time—with one glaring example: his business partner Frank Smith of Newark NJ.

John and Frank went into a small jewelry business in Newark sometime around 1915 or 1916. They had known each other since 1912 and Frank seemed to be financially unstable: he “has been in debt to me since the Spring of 1914.” Nevertheless John went ahead with the partnership with this questionably reliable man. It’s puzzling since John expressed himself as a clear-minded and careful businessman. It was a serious mistake that John came to regret more than any other in his adult life.

Not surprising, shortly after John entered the military in the summer of 1917 Frank secretly sold their business, which John said was doing well: “…and right after I left the business started to boom and it should have kept two <people> busy all winter with the capitol and stock to work out.” As long as John was present things seemed to go well enough: “When I was around him, I had him under control like a child but now that I am away things are different.”

But John left and Frank sold out for about $500, of which $421 was owed to John. Virtually none of the money was put into John’s account, and other amounts of $10 or $20 John had sent Frank from Camp Gordon also were missing from his account. John only found out slowly and through inquiries to his bank. It later came to light that Frank had also forged John’s signature at least once in transactions with the bank.

The confusion and strain of Frank’s betrayal was clearly the most troubling issue for John. There are pages of correspondence to Frank demanding to know what was going on, with apparently few or vague replies from him. These are mixed with reports from other friends that Frank left Newark and traveled either north or south or west as far as California. It’s hard to follow this situation since some of the correspondence between John and Frank and John and other “pals’ who knew them are missing. John tried to enlist Francis to investigate Frank’s dealings but with a family, full time work and slow mail Francis could only offer minimum help.

Of major concern was a diamond ring John had left in Frank’s keeping along with his bank passbook. John at first, trusting Frank, had told him to wear the ring for a while and then send it to Francis for Mame-before Christmas 1917. As the problems with Frank deepened there were frequent demands by John to return the ring. (It was not until December 1918 that Mame finally received it. Perhaps Frank, upon learning of John’s death, felt guilty and surrendered the ring as a small amends to the Ammon family.)

Nothing is said about the money. Understandably, this trouble infuriated John and his most outraged expression came in a letter to Francis in which he said, “I get wild when I think of it.” Frank was clearly “an unfavorable pal…When I get back and if things are settled by him I want to show his many Friends what a four flusher he has been ever since the day they met him. There always comes a time.” Unfortunately John ran out of time. However, there are records that indicate that Francis continued to pursue Frank well into the 1920’s to regain John’s rightful due–about $400.

Departure for the Great War

“Preparing for France is only a matter of weeks and perhaps days. We are all in the dark at the present.” Inspected by the Secretary of War Baker and having trained all winter in the south “puts me under the impression that we will be among the first to go. I for one am ready…” So wrote our young would-be hero, in the springtime of his life, emboldened by patriotism and primed by propaganda that America was off to defend civilization. It was sometime in early May 1918, we believe, that John’s troop ship set sail from New York bound for the north coast of France.

(As of July 2004, we are still awaiting a reply from the military archives in St.Louis, MO regarding John’s service records and the history of his I-Company, 327th Infantry. Further details will be added to this story as we receive them.)

The first notice sent home to Francis was simply a generic post card signifying John’s safe arrival in France: “The ship on which I sailed has arrived safely overseas” was printed, under which John signed his name, “Private John Ammon. I-Company , 327 Infantry. dep. N.Y. City. Will write later, American Expeditionary Forces.” The card was printed by The American Red Cross, ‘Soldiers’ Mail. No Postage Necessary.’

Background to the War

The American Army in 1914 consisted only of a small regular volunteer army of 127, 588 men and a National Guard of 181,620. This force was inadequate to play a significant role on the Western Front, so in May 1917 conscription was introduced and the strength of the army rose to more than 3 1/2 million by 1918. (John signed up on June 5, 1917.)

Due to German hostilities in Europe and on the Atlantic, President Woodrow Wilson asked for a declaration of war on April 2, 1917. It was passed by Congress and signed by the nation’s chief executive four days later.

A very limited Americans force went over in July 1917 as a propaganda gesture. By the Armistice in November 1918, more than 2 million had reached France, although they did not assume a combat role until the last 200 days of the war. Nevertheless, the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) were aggressive and successful and came to hold 160km/100 miles of the western front in France in the early fall of 1918. Twenty-nine of the fourty-two American divisions went into battle, and almost 1 1/2 million Americans saw combat. In the AEF there were 126,000 killed, 234,300 wounded, and 4,500 taken prisoner or missing in action–in less than one year of involvement in Europe.

The French General Foch (supreme commander) and British General Haig had originally envisaged American troops serving as replacement for losses in the British and French armies. For a while this was the arrangement. But the American General John J. Pershing later insisted on keeping US formations ‘as a separate and distinct component of the combined Forces’.

John arrived. presumably at Le Havre port, in early May 1918, two months after the Germans mounted their last desperate offensive toward Paris in March. By the time he arrived there was a lull in the fighting. It’s difficult to say if John’s unit served as a replacement force for the British or French or whether they were part of the all-American force under Pershing. One guess is that John’s company was both, replacement at first then later moved as part of the 2nd Army Corps to the 1st US Army commanded by Pershing.

. . . American troops shipping out for Europe, 1917. . . . American troops shipping out for Europe, 1917. |

Finally, on 30 August 1918, the General “… achieved his purpose of bringing the first American Army into being. It was immediately deployed south of Verdun, opposite the tangles and waterlogged ground of St. Mihiel salient, which had been in German hands since 1914. On September 8 Pershing launched the first all-American offensive of the war. The Germans…were taken by surprise and subjected to severe defeat. In a single day’s fighting, the American I and IV corps, attacking behind a barrage of 2900 guns, drove the Germans from their position, captured 466 guns and took 13,251 prisoners… “

John’s unit was likely a part of the 2nd army corps, which was not mentioned in one text in the descriptions of the St. Mihiel offensive. Only the 1st and 4th corps are mentioned, in one text, as participating in the offensive. From this we might suppose that John’s unit functioned as a reserve force supporting those two combat corps. However, nowhere was safe; artillery could be fired quite a distance behind the front lines by big cannons and many soldiers were killed or injured who were not actually on the front line. (One family story relates that John was killed by such long-range artillery.)

Very soon after the St. Mihiel victory the Allied commander General Foch initiated his own massive counter-offensive to push the Germans back across the Rhine River. The whole front from Switzerland to the English Channel was “ignited” said one source. The Brits in the north, French in the middle and Americans in the south.

The southern portion of the counter-attack was called the ‘Battle of Meuse-Argonne’ (between the Meuse River and the Argonne Forest). The action started on September 26, 1918 with intermittent forward progress but as the Germans brought in reinforcements the battle bogged down by October 10. Nevertheless the superior masses of Allied (British and French) weaponry and American troops kept the Germans on the defensive. On October 14 another initiative by the Americans to break though this last German stronghold of the war. Two days later, according the Western Union telegram to Francis, John was killed.

Thousands of soldiers died in this effort but Germany’s strength was finally broken and the Central Powers started to collapse politically and economically. Talk of surrender was heard in the back rooms of power and within four weeks, on November 11, 1918, the armistice was declared.

The Final Episode

The first frontline letter: July 8th, 1918

Under the ominous clouds of war that overshadowed John’s company in France it is almost comical what he reported in (the first surviving letter) to Francis: “Yesterday were off in the afternoon and most of us went for a swim.” He goes on to say that the swim reminded him of a quip about truant Sunday school boys: ”Being it was on Sunday it reminds me of the minister who asked the boy if he knew where little boys went for swimming on Sunday. ‘Yes sir,’ he replied, ‘come along and I’ll show you.’”

Soldiers in the trench Soldiers in the trench |

He then turns to the more serious situation at hand by explaining, “since I wrote my last letter quiet (sp) a lot has happened that would be of interest to tell but due to strict censorship, this is prohibited.” Indeed the censor’s initials are on all John’s correspondence. (In this paragraph, John refers to one of his two previous letters home which we do not have.)

“We have moved about quiet (sp) since landing and I imagine I have seen a good portion of France already but if you can send me Uncle or Aunts address <in Switzerland> it may be possible for me to look them up during rest period.” The Uncle and Aunts he refers to are the siblings of his father Frederick. (Frederick had died on January 13, 1917, about six months before John entered the army.)

Frederick had a total of six siblings, three brothers and three sisters. By the time John arrived in Europe in May 1918 three sisters and one brother were still living in Switzerland: Elise (1861-1943), Marie-Anna (1865-1935), Marie-Ida (1873-1956) and the brother Johannes (1872-1954). (When Richard Ammon first visited Switzerland in 1964 he visited the graves of two sisters in Schaffhausen. The third sister and the brother were buried in Herzogenbuchsee about 65 miles away. Johannes was the grandfather of the present-day Ammon cousins in Switzerland. After thirty years, Swiss graves are removed to make room for new ones.)

Regarding the ‘moving about’ that John refers to, it’s probable that his company landed in the north of France in May and by the date of his letter, July 8, they had moved south and east toward the Meuse-Argonne area where we believe his regiment was involved in direct or supportive combat, as detailed above. Specific details of course were prohibited from any discussion by troops in the trenches.

The second letter: August 7, 1918

Written on Salvation Army stationary John expresses his regret that he has not heard from home despite two letters from him on May 14 and July 7 (both missing from our files). Nothing was written by him for almost a month, which was unusual for him.

It is likely his unit was actively engaged in combat or supportive maneuvers and/or changing locations with some frequency. He seems anxious and unsettled without regular word from friends and family. These expressions of isolation seem more fervent than ever before, feelings exacerbated by the intensity of his circumstances. In a rare reference to the horror of battle he wrote, with great understatement, “Since I wrote you last I have had a real touch of war and all I can say is that Sherman was right. (The Civil War General’s famous declaration was, ”War is hell.”)

John goes on, “The front line trenches are a busy place at times, that is when we are ducking shell fire. Most of us are on guard at night although someone is always on the lookout from the observation post. So many days are spent in the front trenches, then we go back to the rest camp for so many days, and then up to the support line trenches “which are about a mile behind the front ones” <John’s quotes> for so many days, and so on over and over again. Sometimes a group of us get together and take a trip over no man’s land just to see what the Huns are getting ready to do. This is called night patrol.

Painting of American battle at Chateau-Thierry, July 1918 Painting of American battle at Chateau-Thierry, July 1918 |

“So far our weather has been cool and no hot days or nights to make us uncomfortable. The farmers are just cutting wheat and rye and most of it is done with the cradle. Most of the machines over here are American make.”

“So far I have seen a few fruit trees in the various parts of the country. The fruit is bad and the trees all appear to be sick. Blight, scale or Gas effect. The crimson clover over here is thicker and better than any red clover I ever saw in the States

“Writing letters is such a difficult task. There is plenty to tell but the censor will not allow to (sp) much war news to go through. John most likely refers here to the frustrating task of not being allowed to write about the resounding violence and terrible carnage surrounding him. (Today, one can readily see in 21st century days of televised and cinematic warfare, the shattering experiences of front line soldiers.)

“By this time you have read of the Allied advance at Chateau Thierry. The greatest drive the Allies have made since the war started. Things look good for the allies but I believe we still have a long hard row to hoe.

“The pen, paper and ink are all so poor it is difficult to write a nice clean letter but I trust you can read it.” He signs off for the first time using “with love to all. Each day finds me well and in good spirits.”

John’s reference to Chateau-Thierry was the only specific engagement he specifically named in his letters. It was a crucial battle in the final months of the war. The Germans attempted to push through another salient (forward line) toward Paris and the French alone could not stall them. On July 15, 1918 the Allied commander wisely gave the green light for a major all-American army offense against the German force at Chateau-Thierry and this turned the tide as the Americans routed the Germans. It was the beginning of the end but there was a high cost in young blood, with more to follow.

The final letter: September 5, 1918

John chats about the weather for a few lines then writes in appropriately vague terms “we have been very busy of late doing most everything that will help win he war. Note the drives (July and August 1918) by the Allies that are going on at this writing.”

We have to wonder at John’s words when he says, “While I have not been into anything extremely active, still I hope to be in the thick of the fight in the near future, so I want to write all I can while I have time.” These calm and confident words may have been intended to minimize his family’s worries, but they appear to belie the daunting reality in which he was tangled.

In the next few sentences of this letter he opened up more than ever before about the truth of war and the constant life threatening events that confronted him hourly and daily on the front: “ How short the days are getting. Perhaps we notice more than you do, because we go into the trench at dusk and stand until dawn a stretch of nine hours, rain or stars.

American 23rd Infantry Regiment, American 23rd Infantry Regiment,in action at Belleau Wood, France, June 3, 1918 |

“No one dares to go to sleep, but we must continually <be> on the alert. The Huns send over patrols which consist of around twenty men and these are the ones we are always expecting. They also have raiding parties which may run from fifty to 200 men. These fellows work to surround our trench position and try to take you prisoner. We stand together in groups of from one to three men on posts.

“Many times when we are stationed in the woods we are not near enough together too see one another’s position. I work an automatic rifle which shoots many hundred shoots per minute and I feel quiet (sp) safe behind it and very much at home. I take good aim and knock ‘em all dead. No comrade stuff for mine as long as I have ammunition.

“I have heard of them staying behind a machine gun as long as possible and then throwing up their hands to surrender. In some cases they have a bomb they throw as their hands go up, other times they have a string attached to their foot to set their machine gun in motion as you approach to take them prisoners.

“Sometime ago we had quiet (sp) a fortunate escape. Shortly after we were relieved the Huns through <threw> over a gas attack of muster (sp) gas. This gas is wet and does not vaporize until the heat strikes it. Some of it can land on your clothing and if it is cool no danger will occur. You may go about for hours and soon you begin to feel faint, and then the trouble begins. These boys that were gassed got their masks on quick enough but took them off to (sp) soon.

“I continue to be well and strong each day. Nothing seems to worry me, gas or shell, although I do not try to see how brave I can be. It does not pay.

“We were digging a dugout recently and one lad was bothering me fearfully to work hard to get it finished. We were in sight of the Hun observation baloons (sp) and with their strong glasses it was possible for them to see us and direct the artillery in our midst. So you can see how fidgety some are. Some run when they hear our big guns go off behind the lines…we dare not have lights on account of bombs and being busy all day you can see that writing time is short.”

His final line is: “Write when you can. Remember me to the Children, Cora and all. John”.

His words speak for themselves, even in restraint, of the intense danger and harrowing days and weeks of his final weeks. His writing reflects an incredibly stable and courageous personality as he looked into the jaws of his own destruction. (“Nothing seems to worry me, gas or shell…”) Thereafter was silence.

Post Mortem

In that silence Francis was worried. We have only one letter from Francis to John in the years his service. It was written on November 19, 1918. John’s last and longest letter home, as far as we know, had been written September 5, followed by almost 2 1/2 months with no word from him. Francis’ first line expresses his concern: “Dear Brother, Have not heard from you in so long a time that I am beginning to wonder where you are. If you are still on top let me know… Monday was a great day over the signing of the armatice (sp). Was not much work done on that day. The <Hercules> powder works <where Francis worked for 38 years> made a sharp reduction of force laying off over 500 men. It came so sudden no one was looking for it. If it was spring it would make so much difference. I do not expect to be laid off, am glad of that. Do you think you will be home for Xmas?…”

In a cruel stroke of coincidence, Francis did get a reply four days after sending his worried letter, but it was not from John. It was a terse Western Union telegram out of Washington, D.C.: “Deeply regret to inform you that Private John Ammon Infantry is officially reported as killed in action October Sixteenth. (Signed) Harris, The Adjutant General, 4:40 P.M.”

The shocking telegram arrived November 23, 1918. We can readily imagine Francis’ and the family’s first hours and days after reading this heart-rending news. Francis was 31 years old; he probably withdrew to his workshop and cried alone. Cora was 33 and Mame was 33; no doubt they shed tears together and with the children. John, the beloved one, was gone

For the oldest children of Francis and Cora, Ethel (8) and Roger (6) the loss was no doubt painful as well as confusing since they could hardly comprehend the true horror of war. Doris was only three when John left for the service and Grace was about five months old. Neither had a vital memory of John. When the telegram arrived Cora was pregnant with Marian (born June 6, 1919) and Elinor came along three and a half years after that on December 5, 1922. (Francis lived to the age of 82 and died in 1969. Cora survived him by two years and died in 1971 at the age of 85. Mame died in 1964 aged 79.)

Mame’s children were older, Bill was 13 and Eddie 9, so they would have been more aware and felt the loss more keenly perhaps than Francis’ children. But the personal impact of this dire family trauma on every family with any memory of John had to be daunting.

Children of Francis and Cora, November 1917: Children of Francis and Cora, November 1917:(l-r) Doris, Ethel, Roger, Grace |

There is no record of a memorial service for John arranged by his family or friends. Given how much he was esteemed and loved it is likely there was some kind of remembrance observed, porbably in Newark where most of his contemporaries lived, and/or a service was held in the Succasunna Presbyterian Church where the Ammon family attended. Most likely this would have been in November or December, 1918.

Among the various official documents Francis received from the government at this time regarding John’s affairs, there is one curious piece of paper. It’s a receipt for John’s diamond ring signed by Mame on December 18, 1918. It’s clear that John wished for a long time that Mame be given the ring but it had been in the possession of Frank Smith, John’s disreputable business partner. Is it a mere coincidence that the ring was surrendered by Frank at this time, just over a month after public notice of John’s demise? It’s not likely Frank attended a memoral for John since he was now known to be a thief and forger. Nevertheless, Frank had been close with John and he probably saddened by the loss. It’s possible he felt also regret over his dishonest business deal and sent the ring to Francis as a token of his feelings. In turn, Francis offered it to Mame, as accorded in John’s will. This speaks well of Francis as he surely would have liked the ring as a heartfelt remembrance of his brother—and probably his best friend.

Final Arrangements

John was first buried at the American Cemetery at Ardennes-Sommerance in France. The American Red Cross sent Francis a card and a photograph of John’s grave: “with deep sympathy in your loss The American Red Cross sends you the photograph of the grave of this American Soldier who gave his life for his country.” On a simple white wooden cross, #21, John’s name is stenciled on the horizontal arm, although his name was misspelled “John Ammons”. Behind his cross are seen hundreds of other similar crosses of many other young men.

There are numerous extant documents pertaining to John’s will and the legal procedures for paying out its terms. Francis wrote to the War Department in Hoboken, NJ asking for any personal items of John’s. After many months he received a form from the Effects Bureau, Governors Island, NY along with John’s basic items including: “Letters, 1 Testament (Bible?), 1 post card, 3 razors, 1 shaving brush, 1 knife, 1 pencil, 1 strop, 1 pocket book, Miscellaneous papers and 50 centimes.”

By March 2, 1919 the War Department was in contact with Francis about the disposition of John’s body. The French were quite willing to have him rest in Europe but the choice was up to the family.