(Part 1)

Male ‘Homosexualities’ In India & South Asia: Culture, sexualities, and identities: men who have sex with men in India.

By Shivananda Khan

Journal of Homosexuality

Vol 40 (2001)

This essay focuses on men who have sex with men, and gay men. This is because most of the research and analysis conducted so far by the Naz Foundation has been on the male to male sexual behaviors as a significant factor in STD/HIV transmission in India. This is a different matter than the construction of men’s sexualities.

Prem is 26, married, and has a young son. He does not call himself homosexual; the word gay he doesn’t understand, not having access to English. Nor does he see anything wrong with what he does. He is just “messing about.” He remembers his first sexual experience with his uncle back in his home village. He was 12.

Mohammed, 42: “So when I am hot and don’t have enough money, then I know several men who I can have ‘maasti’ with. A lot of my friends do this.” (Maasti is a Hindi term which means mischief and often has sexual overtones when it is used between young men.)

They don’t consider themselves as different. They know many men who enjoy sex with other men. They don’t play husband and wife roles, thinking it rather silly as both are men. Neither read or speak English.

Who is gay in an Indian context? What is gay? Who is homosexual?

About three-quarters (72%) of truck drivers in North Pakistan who participated in a recent survey published in AIDS Analysis Asia admitted that they has sex with other males, while 76% stated that they had sex with female sex workers. Are these 72% gay? Homosexual? There is sufficient anecdotal evidence to indicate that in the other countries of the sub-continent, similar levels of male to male sexual behaviors exist as part of a broader sexual repertoire. Are these males bisexual?

In working with sexual health issues in India and in listening to the rhetoric of UNAIDS representatives, international donor agencies, the Indian medical profession, and many Western and Indian gay men, an assumption is often made that same-gender sexual behaviors must mean the person is a homosexual, or gay, while male to female sexual behavior must mean that the person is heterosexual.

In these discourses, procreative “heterosexuality” is seen as ‘normal.” While other behaviors are seen as perverse or foreign. However, these constructs seem to have little contemporary or historical validity in India (and even to some extent in the West). This reductionist ideology is a recent invention from the 19th century, which has consequently acted to reduce the rich diversity of alternate sexualities (Foucault, 1978; Weeks, 1986; Katz, 1995, Herdt, 1994).

In these discourses, procreative “heterosexuality” is seen as ‘normal.” While other behaviors are seen as perverse or foreign. However, these constructs seem to have little contemporary or historical validity in India (and even to some extent in the West). This reductionist ideology is a recent invention from the 19th century, which has consequently acted to reduce the rich diversity of alternate sexualities (Foucault, 1978; Weeks, 1986; Katz, 1995, Herdt, 1994).

Closer analysis of these debates seems to me to indicate a confusion among the terms sexual behavior, gender, identity formation, and cross-cultural validity, and within such confusion there may well be elements of neo-colonialism, racism, and Western imperialism (Khan, 1994c; Hyam, 1990).

I was interested to hear Dede Oetomo, a gay activist in Indonesia, say at the Vancouver International AIDS Conference in July 1996 that perhaps “importing” Western constructions of gay identities into Indonesia was creating a social tension whereby local homo-affectionalist and homo-social structures were being destroyed for the fear of being labeled “gay.”

The debate on sexualities may even at times be perceived as a form of neo-colonialism whereby Western sexual ideologies have “invaded” Indian discourses on sexuality and identity by professionals, laypersons, “straights” or “gays,” and whereby indigenous histories and cultures become invisible.

Much same-sex sexual behavior involves non-penetrative varieties, mutually indulged in frameworks of friendships and sexual play, while in other situations urgent sexual discharge and sexual “need” is the significant factor.

However, the denial of variation in history in many Western and Indian discourses had given rise to a prevailing construction of sexuality, where a “procreative and penetrative” sexual ideology is the only “sexuality” that is seen as relevant. Perversely, any other form is categorized as deviant and Western.

Opportunities like this are frequent and mean that significant amounts of male-male sexual behavior occur within family environments and networks, between male relatives and friends. But this is not seen as real sex! This is maasti, invisible and denied.

Opportunities like this are frequent and mean that significant amounts of male-male sexual behavior occur within family environments and networks, between male relatives and friends. But this is not seen as real sex! This is maasti, invisible and denied.

The following comment made to me by a man in New Delhi captures the context of much sexual expression in India: “Privacy? What privacy? I share a room with three older brothers, and I have sex with all of them.”

—————-

(Part 2)

A second academic comment about male sexuality is by S. Asthana and R. Oostvogels: The social construction of male homosexuality’ in India: implications for HIV transmission and prevention. Published in ‘Social Science & Medicine’, vol 52(2001).

Excerpts:

[Noted is that the western discourse on sexuality to be based on the] “heterosexual/homosexual dichotomy,” [and that such perceptions do not necessarily apply in other cultures]. However, in many cultures, homosexuality is not recognized as a socially significant category and although male homosexual behavior is prevalent, it is not associated with a specific ‘gay identity’.

[Although the concept of MSM (men having sex with men) has been used in the West], “In practice, however, MSM is often use interchangeably with that of ‘gay men’.”

Thus, whilst there was more social acceptance of alternative sexual natures in the 1970s and more space emerged for sexual minorities to live their lives without repression, gay men also became more sexually isolated. Due to the tendency to to associate male homosexuality with effeminacy, men who wished to preserve their masculine heterosexual self-image withdrew from homosexual circuits. Thus there was a decline in the proportion of men who had sex with men who were also involved in heterosexual relationships. The fact that the affirmation of one’s homosexuality became the basis of positive social identification also contributed to the view that bisexuality was an illegitimate socio-sexual identity. The rejection of the effeminate stereotype was also part of the gay political agenda.

From the beginning, AIDS was associated with sexual deviance, heterosexuals who contracted HIV/AIDS being treated either as ‘innocent victims’ or as nominal queers (citing Goldin, 1994; Patton, 1994)

…the Indian system differs from the Latin American form of patriarchy which, in addition to defining a passive, self sacrificing and dutiful role for women, represses femininity in men and promotes aggressive manliness (Almaguer, 1993; Lancaster, 1995).

…the Indian system differs from the Latin American form of patriarchy which, in addition to defining a passive, self sacrificing and dutiful role for women, represses femininity in men and promotes aggressive manliness (Almaguer, 1993; Lancaster, 1995).

First, the status of women in marriage and the norms and traditions controlling their behavior so clearly establish male superiority that Indian men do not have to strongly assert their masculine characteristics in order to be thought of as ‘male’. Second, the social position of men in influenced by their caste position. These factors may in part explain why there is no need for a system such as Latin American Machismo to provide a means of structuring power relations between men.

…providing that a man does not adopt an alternative gender identity, he may engage in ‘homosexual’ activity without compromising his masculinity…the taboo on pre- or extra-marital sex for women is more strictly enforced than the taboo on homosexuality.

However, due to the social distances between the sexes, men who also seek sexual fulfillment in relations with other men. Indian culture is highly homosocial and displays of affection, body contact and the sharing of beds between men is socially acceptable (Kahn, 1994) This creates opportunities for sexual contact, though sexual behavior in this context is rarely seen as real sex, but as play. Much of this same-sex sexual activity begins in adolescence between school friends and within family environments and is non-penetrative.

Young men who cultivate such relationships do not consider themselves to be ‘homosexual’ but conceive their behavior in terms of sexual desire, opportunity and pleasure… Given the constant expectation that a man will eventually marry and produce sons, he can enter in same-sex sexual relations without challenging his masculine sense of self… Even effeminate men who have a strong desire for receiving penetrative sex are likely to consider their role as husbands and especially fathers to be more important than their self-identification than their homosexual behavior.

Thus, to be receptive in homosexual encounters does not necessarily denote loss of manhood. Nor does it imply passivity and a subordinate class. This aspect of male-male  sexual relations in India differs markedly from other contexts such as Latin America (Parker, 1991; Almaguer, 1993). And the Middle East (Tapinc, 1992) where active / passive and dominant / subordinate meaning are associated with sex role. Instead, emphasis is placed on giving and receiving pleasure. This allows for a greater equality of status between partners.

sexual relations in India differs markedly from other contexts such as Latin America (Parker, 1991; Almaguer, 1993). And the Middle East (Tapinc, 1992) where active / passive and dominant / subordinate meaning are associated with sex role. Instead, emphasis is placed on giving and receiving pleasure. This allows for a greater equality of status between partners.

The principal method in the research was therefore participant observations, first covert then revealed. A team of three researchers was formed, all of whom had a background in social science. [The various categories of men who engage in same-sex sexual activities in so-called “sexual circuits” in Madras are given.

As with Indian men and women, a social distance exists between masculine- and feminine-identified MSM and it is difficult to envisage a fundamental change in these arrangements – e.g. the development of more reciprocal social and sexual relations. It is therefore highly unlikely that a collective ‘gay’ consciousness and solidarity can be achieved in the Indian context. Indeed, care should be taken in assuming that an incipient ‘gay movement’ already exists in the country (Drucker, 1996).

[Of all the categories of MSM}… Double deckers also represent the only category of MSM in Madras for whom North American/West European model of gay activism may have some meaning.

Conclusion:

There is thus a pressing need for more research on the ways in which the sexuality and sexual conduct of MSM vary cross-culturally. For some 20 years, social construction theory has set an example of how such research could proceed (Vance, 1991). For most part, however, this perspective has been elaborated in debates on gay and lesbian politics or in historical studies of sexuality and relatively little work exists which applies constructionist approaches to the study of HIV/AIDS. We hope that this paper has demonstrated that, if appropriate and effective HIV interventions are to be developed, more attention should be paid to the socio-cultural context and organization of sexuality and sexual activity.

Among the educated middle classes, there is a small, but growing, movement of people whose sense of personal identity is separate from that of their family, kin group, and community and who are beginning to create new forms of sexual identity. Many of these may well call themselves lesbians, gay men, homosexuals, bisexuals, and even heterosexuals. In the main, these evolving and emerging identities are arising with the growth of urban, industrialized, and commercial cultures (including the Internet) , concomitant with which is a rising sense of individuality, personal privacy, and private space.

Among the educated middle classes, there is a small, but growing, movement of people whose sense of personal identity is separate from that of their family, kin group, and community and who are beginning to create new forms of sexual identity. Many of these may well call themselves lesbians, gay men, homosexuals, bisexuals, and even heterosexuals. In the main, these evolving and emerging identities are arising with the growth of urban, industrialized, and commercial cultures (including the Internet) , concomitant with which is a rising sense of individuality, personal privacy, and private space.

This cultural change appears to be associated with the development of nuclear family lifestyles, the expansion of education, and the power of the English-speaking middle-classes to access Western literature and to make more choices about their lives. It is mostly people from these backgrounds who meet, socialize, discuss and debate (usually in English) issues of sexual identities and “coming out.” Gay activism in India is growing and has begin to challenge laws which criminalize homosexuality and which were inherited from the British Raj. It remains to be seen whether these emerging identities will reflect (or perhaps imitate) Western constructions and whether those who adopt these identities will attempt to live these out within Indian cultures, or whether differing identities will be constructed.

References:

=Almager T (1993). Chicano men: a cartography of homosexual identity and behavior. In H. Abelove, M. Barale, and D. Halperin, Eds. The lesbian and gay studies reader, 255-73. London: Routledge.

=Goldin C (1994). Stigmatization and AIDS: critical issues in public health. Social Science & Medicine, 39(9): 1359-66.

=Kahn S (1994). Cultural contexts of sexual behaviors and identities and their impact on HIV prevention models: an overview of South Asian men who have sex with men. Indian Journal of Social Work, LV(4): 633-46.

=Lancaster RN (1995). ‘That we should all turn queer?’ Homosexual stigma in the making of manhood and the breaking revolution in Nicaragua. In RG Parker, and JH Gagnon, Eds. Conceiving sexuality: approaches to sex research in a postmodern world, 135-156. London: Routledge.

=Parker RG (1991). Bodies, pleasures and passions. Sexual culture in contemporary Brazil. Boston: Beacon Press.

=Patton C (1994). Last served? Gendering the HIV pandemic. London: Taylor & Francis.

=Tapinc H (19992). Masculinity, femininity and Turkish male homosexuality. In K. Plummer, Ed. Modern homosexualities:fragments of lesbian and gay experience, 39-49. London: Routledge.

=Vance CS (1991). Anthropology rediscovers sexuality: a theoretical comment. Social Science & Medicine, 33(8): 875-84.

————————-

(Part 3)

‘Same-Sex Love in India’ by Saleem Kidwai and Ruth Vanita.

This recent book is a landmark study by two gay scholar-authors whose work has been widely received and much needed to bring clarity and light to the study of homosexual love and behavior in ancient and modern India.

This recent book is a landmark study by two gay scholar-authors whose work has been widely received and much needed to bring clarity and light to the study of homosexual love and behavior in ancient and modern India.

Interviewer Raj Ayyar has said: “there are many in the West as well as in India and elsewhere who see homoeroticism as a ‘Western import.’

“This false cliche held by colonialists and post-colonial ultra-nationalists, by right-wingers and leftists of whatever stripe, is powerfully challenged in ‘Same-Sex Love in India’ by Saleem Kidwai and Ruth Vanita.

“In this book the authors have done a great job of uncovering gay texts throughout Indian history, from the ancient Hindu Shastras to the present…”

“In this book the authors have done a great job of uncovering gay texts throughout Indian history, from the ancient Hindu Shastras to the present…”

Extensive interviews with these two gay teacher-authors can be read at the following pages:

Interview with Ruth Vanita (pictured at right)

Interview with Saleem Kidwai(pictured above)

—————————–

(Part 4)

A third interview, by Perry Brass, is with one of India’s best known gay activists Ashok Row Kavi. He writes: “Ashok Row Kavi, the most famous gay activist and theorist in India today, has long been known for coming out openly both as a gay man and an activist in the Indian AIDS struggle

“He has been called the ‘Larry Kramer of India,’ though in person and in print he is more humane, understanding, and endearing than Kramer. But like Kramer, he has lots of opinions, and many of them land squarely on the issues involved—much more so, I would say, than most people trying to figure out India itself, an almost impossible situation.

“He has been called the ‘Larry Kramer of India,’ though in person and in print he is more humane, understanding, and endearing than Kramer. But like Kramer, he has lots of opinions, and many of them land squarely on the issues involved—much more so, I would say, than most people trying to figure out India itself, an almost impossible situation.

“He is the editor of Bombay Dost (“Bombay Friend”), the only gay magazine published in India, which is now published on an irregular, quarterly schedule…”

…and he is much more in addition to being an activist and editor.

Interview with Ashok Row Kavi (pictured left)

All three inteviews are courtesy of Gaytoday.com (http://www.gaytoday.com/

——————–

(Part 5)

India’s Sexual Minorities–Gay Parade in Calcutta a mark of changing mind sets

The Statesman, Kolkata, India

( http://www.thestatesman.net ) http://www.thestatesman.net/page.news.php?clid=3&theme=&usrsess=1&id=18938

July 27, 2003

Homosexuality emerged from the closet with the gay march in Kolkata on June 29. Its public face is a mark of changing mind setsBy Swagato Ganguly

Globalization is creeping, even if on tiptoe, to a conservative city like Kolkata. I refer not to swanky shopping malls, styled like their counterparts abroad. I refer to a march by gay men in support of homosexual rights on 29 June, a first in Kolkata. It began, and wound its way through, impeccably middle class localities: Park Circus, Gariahat Road, Gol Park. I do not want to make the claim that homosexuality is a global import unknown in traditional cultures. Same-Sex Love in India, a recent book by Saleem Kidwai and Ruth Vanita, catalogues a whole bunch of references to, if not homosexual, at least homo-erotic passion in traditional Indian texts. I do agree, however, with French philosopher Michel Foucault, himself a homosexual, that heterosexuality and homosexuality as distinctive lifestyles are a modern Western invention.

It is not that homosexual acts were unknown in non-Western cultures; what was unheard of was that anyone should predicate his or her whole being, and identity, on being homosexual. But that was what the marchers of June 29 were effectively doing. In traditional cultures, including India, men might have relations with other men while simultaneously leading married lives and having children. Although, as Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai have shown, there are references to homoerotic behaviour in premodern Indian texts, homosexual conduct is rarely spoken of approvingly, and judgments on female homosexuality are particularly harsh.

It is not that homosexual acts were unknown in non-Western cultures; what was unheard of was that anyone should predicate his or her whole being, and identity, on being homosexual. But that was what the marchers of June 29 were effectively doing. In traditional cultures, including India, men might have relations with other men while simultaneously leading married lives and having children. Although, as Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai have shown, there are references to homoerotic behaviour in premodern Indian texts, homosexual conduct is rarely spoken of approvingly, and judgments on female homosexuality are particularly harsh.

The same social arrangement continues, in effect, in the present day. There exists an underground subculture of homosexuality which is not violently persecuted in India. Homosexuals, on their part, must ensure their activities aren’t too overt and intrude into the public sphere. That implicit social contract was violated when gay men took part in a public procession on June 29.

It must be noted, though, that there were no lesbians in the march, although the topic has been aired in films and books from time to time. The emergence of homosexuality into the public sphere is still a hesitant affair.

What makes modern homosexuality shocking to many is its refusal of the “obligation” to procreate. Anyone who believes that the core of his (or her) being lies in his/ her relationship with another person of the same sex is, ipso facto, forswearing his/her “responsibility” for propagating the tribe/ community/ nation/ society. In other words, along with modern homosexuality, the modern individual is born. In any traditional culture, one of the biggest imperatives is to multiply its members. A community’s numbers may be depleted by nature’s depredations and by war. Replenishing those numbers is a primary need; individual rights and desires come a poor second. Thus the Bible says “go forth and multiply”; for Hindus peace in the afterlife isn’t possible unless funeral rites are performed by one’s offspring.

Modern culture, by contrast, has acquired sufficient control over nature to make overpopulation, rather than under population, a problem. And as far as war is concerned, a million men do not count for much when faced with a single intercontinental ballistic missile, which makes gaining access to the latter a rather more important factor in contemporary power politics. There has thus been a loosening, in the last half-century or so, of the taboo against non-procreative partnerships.

If consumerism makes possible an expanding array of lifestyle choices, and an individual is defined by the choices he makes, then there are alternate sexualities one can “consume” as well. It is in that context that the emergence of sexual minorities becomes a marker of incipient globalization.

If consumerism makes possible an expanding array of lifestyle choices, and an individual is defined by the choices he makes, then there are alternate sexualities one can “consume” as well. It is in that context that the emergence of sexual minorities becomes a marker of incipient globalization.

Take the occasion that Kolkata’s marchers were commemorating on June 29, along with marchers in Sao Paulo, San Francisco and other cities across the globe. The occasion was the Stonewall riots in New York’s Greenwich village in 1969. On June 27, 1969, New York police raided the Stonewall Inn, a popular gay bar in Greenwich village. While such raids had been routine, on that occasion the crowds fought back, and the neighbourhood erupted in riots and protests for the next few days. That sparked the worldwide gay rights movement which has become a facet of contemporary modernity.

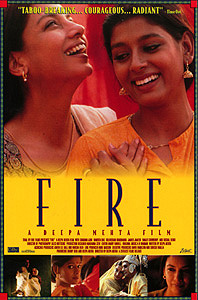

Many might scent dark neo-imperialist conspiracy here, as raids on gay bars are not yet a local issue in India. But what is a local issue, undoubtedly, is the existence of Section 377 on the statute books, according to which homosexuals can be awarded imprisonment for up to 10 years. And sooner or later the issue might capture the attention of the neo-Hindu right which is obsessed, after all, with questions of numbers and demographics. A marriage between Article 377 and a conservative BJP-type government could yield as offspring some serious persecution of sexual minorities. The ire visited by the Shiv Sena upon ‘Fire’, a film depicting a lesbian relationship between two women, can be a precursor of things to come.

While West Bengal’s Left Front government might be right up there with anyone else when it comes to the suppression of individual rights and the persecution of dissent, it must be placed on record that it did provide police protection and didn’t allow untoward incidents in the case of the marchers of June 29.

While West Bengal’s Left Front government might be right up there with anyone else when it comes to the suppression of individual rights and the persecution of dissent, it must be placed on record that it did provide police protection and didn’t allow untoward incidents in the case of the marchers of June 29.

If the backlash against homosexuality can be attributed to its privileging the modern individual over the social “necessity” to procreate, 21st century biotechnology could bring about a fascinating twist in this tale. I am not referring to cloning where, besides the complex ethical issues that it raises, the characteristics of only one “parent” among a homosexual couple would be transferred.

But can there be a procedure where a homosexual couple can have a child who will inherit the genetic material of both parents, just as the children of “normal” heterosexual couples do? The answer to that question appears to be yes. An experiment carried out with mouse eggs, and reported in the journal Science, raises that very possibility if duplicated with human eggs. In the procedure, called egg nuclear transfer and initially conceived to help infertile couples, the DNA from a damaged egg can be evacuated and placed in another egg, whose own DNA has been removed. In theory, the same procedure can be used to introduce sperm DNA into an evacuated egg, fertilize this “male egg” with sperm from another parent in the laboratory, then gestate the resulting embryo in a surrogate mother.

The baby born would have the genetic material of two male parents. The same procedure could be repeated for two female parents. If this or similar procedures of mixing human DNA were to become widespread in another fifty years, an offshoot would be that homosexual couples could become parents and have families just like everyone else.

That would, of course, force us to radically revalue our concepts of “motherhood” and “fatherhood”. It would do away with one problem, though. If the unconscious resistance to homosexuals stems from the fact that they do not contribute to society’s imperative of reproducing its members, that wouldn’t hold anymore. Radical individualists might rue the loss of homosexuality’s subversive charge, but it would lead to the integration of homosexuals into society, to the extent that even mashima and pishima might not take much notice of the family with same-sex parents living next door.

Note: For more intimate insights about the ‘inner’ lives of LGBT people I suggest the following sites: Movenpick: http://www.orinam.org/comingout.html and Gay Bombay Yahoo Group: www.gaybombay.org.

Also see:

Islam and Homosexuality

Gay India Stories

Gay India News & Reports 2000 to present

Gay India Photo Galleries