(Updated January 2007)

A Hub of World History

Potsdam, Germany, a suburb of Berlin, is memorialized in modern times by the famous conference that took place from June to August 1945.  Here the three conquering powers from the USA, Britain and the Soviet Union sat down to disarm and divide the broken Nazi Empire. Truman, Churchill and Stalin, wielding their pens, ended the dream of Germanic superiority over all of Europe.

Here the three conquering powers from the USA, Britain and the Soviet Union sat down to disarm and divide the broken Nazi Empire. Truman, Churchill and Stalin, wielding their pens, ended the dream of Germanic superiority over all of Europe.

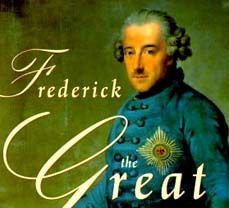

This was certainly not the first time that neighboring nations had to deal with a powerful military leader who threatened the political and geographic stability of the continent. Almost exactly two hundreds years prior, the enigmatic and brilliant Prince Frederick ascended the throne of Prussia (roughly modern day Germany and Poland) to become King Frederick II, known in history as Frederick the Great.

His remarkable talents, which were many, included highly advance skills in architectural design and writing music. His legacy in this art is enormously present today in Potsdam. Set in a magnificent 717-acre park called Sans Souci (‘without worry’), are palaces and landscapes designed and built by Frederick (along with his architects) over a period of twenty-five years. These include two of Europe’s grandest palaces that still drip with Rococo opulence.

Among the countless details of the park and buildings are, to the keen gay visitor, numerous masculine statues extolling the beauty of the male figure. No doubt Frederick felt inspired by Greek and Roman artisans who also admired the power and beauty of “l’homme naturel”.

The story of this enlightened despot who loved literature, music and men while thrashing his way through horrific wars is told in the book ‘Gay Men and Women Who Enriched the World’ by Tom Cowan (1996). The balance of this story is directly quoted from that source.

Early Traumatic Love and Loss

While on a trip with his father in August of 1730, Frederick, the 18-year-old crown prince of Prussia, and his lover, Lieutenant Hans von Katte, plotted their escape to England. The two were caught, imprisoned, and court-martialed for desertion. Because of the two men’s high status in the army and their noble backgrounds, the death penalty was not advised.

But King Frederick William I  took the occasion to teach his son a lesson about what he called the boy’s “unmanly, lascivious, female occupations, highly unsuited for a man.”

took the occasion to teach his son a lesson about what he called the boy’s “unmanly, lascivious, female occupations, highly unsuited for a man.”

In defiance of the court, the king personally ordered that the 26 year-old Katte be executed. In the early morning hours, as the young officer and former royal bodyguard was led to his death, the prince was awakened and forced to go to the place of execution.

When he realized what was about to happen, he blew his friend a kiss and said, “My dear Katte, a thousand pardons, please.” The lieutenant replied, “My prince, there is nothing to apologize for.” Refusing the blindfold, Katte was then beheaded.

Royal Abuse and Natural Talents

The execution of Katte was the ultimate insult in a long history of physical and psychological abuses inflicted on Frederick by a stern, puritanical, and brutish father. Complaining that he could never figure out what secret thoughts inhabited his son’s brain, the king frequently whipped or caned Frederick before servants and officers. On one occasion he tried to strangle the boy. Beatings were normal occurrences in the king’s attempt to break his son’s resolute will. But the boy remained firm. When his father tried to force Frederick to give up his right to succession in favor of a younger brother, he refused.

The clash of wills between father and son extended back into Frederick’s childhood, when a French-Swiss tutor encouraged and nurtured the young prince’s native intelligence and artistic talents. In the end, the king was no match for his exceptionally bright son.

On his part, Frederick found his father’s military and hunting interests dull and boorish. His own pastimes centered on books and the arts, the “female occupations” which his father thought unmanned him for statecraft.

When it became clear that the 16-year-old prince and a royal page, named Keith, had an ongoing sexual relationship, Frederick William assumed that Prussia itself would suffer should his son inherit the throne. Even after Katte’s execution two years later, Frederick insisted on his right to the throne. Finally his father relented; and under a severe surveillance which amounted to house arrest, Frederick was trained for royal duties.

Affairs of State

In 1733, three years after the aborted escape attempt, the king arranged a political marriage for Frederick to Princess Elizabeth Christine of Brunswick. Frederick wrote his sister  Wilhelmina that he found his fiancée repugnant. “We have neither friendship nor compatibility,” he wrote. And, he added, “She dances like a goose.” But the arrangements proceeded. The marriage produced no children, which has led some historians to surmise that it was unconsummated. Never relishing the company of women, Frederick gave his bride her own palace, refused to allow her to live in his other residences, and visited her infrequently, usually only a few days at Christmas.

Wilhelmina that he found his fiancée repugnant. “We have neither friendship nor compatibility,” he wrote. And, he added, “She dances like a goose.” But the arrangements proceeded. The marriage produced no children, which has led some historians to surmise that it was unconsummated. Never relishing the company of women, Frederick gave his bride her own palace, refused to allow her to live in his other residences, and visited her infrequently, usually only a few days at Christmas.

The king eventually relented enough to give Frederick a residence of his own at Rheinsberg, along with a regiment. The four years at Rheinsberg from 1735 to 1739 (Frederick was aged 23-27) were the pinnacle of his education and military training. Here Frederick saw to his military duties, studied philosophy, read literature, composed music for the flute (over 100 sonatas and concertos in his lifetime), wrote poetry, gave parties, sponsored theatrical presentations, and soaked up the cultural and intellectual trends of the French Enlightenment. He devoured Voltaire, and began a correspondence with the French philosopher that would span 42 years and comprise over 1,000 letters.

The Rheinsberg court was composed of soldiers, philosophers, scientists, writers, and artists. It was an exceedingly masculine environment based on friendship and self-development. Absent were the excessive hunting, drinking, gambling, and womanizing that characterized most eighteenth-century European courts. Frederick held himself to a stringent schedule of waking at four a.m. (he needed only five to six hours of sleep a night) and studying or working until noon. Often he read till after midnight. In the process, he became the most knowledgeable and sophisticated prince in Europe.

Becoming His Own Ruler

In 1740, Frederick William died, and the 28-year-old Frederick became King of Prussia.  He wrote to Voltaire that he would now reluctantly have to bid farewell to music, poetry, and pleasure. And so it seemed.

He wrote to Voltaire that he would now reluctantly have to bid farewell to music, poetry, and pleasure. And so it seemed.

In October of that year, the 23-year-old Maria Theresa ascended the Austrian throne, and Frederick took the opportunity to strike a lightning raid for the Austrian territory of Silesia, the first in a series of “lightning wars” that became a model for Prussian military strategy. In his first assault, the lightning struck slowly, but when the War of the Austrian Succession finally ended, in 1748, Silesia was under Frederick’s rule.

In the course of his long reign of 46 years, Frederick’s military prowess and courage became the envy of all Europe. His unpredictable lightning strikes changed the slow, mechanical style of warfare forever, as he developed and used the offensive maneuver far beyond the customary standards of his day. Also, allies and enemies alike studied and imitated his strategy of attrition, a tactic of inflicting repeated blows against an enemy army until it lost the will to fight. Frederick became the preceptor of modern warfare and made Prussia a feared military power.

Reforms of State

Frederick’s enlightened despotism lifted Prussia out of the Middle Ages and laid the course for her entry into the family of modern nation-states. He abolished torture and other extreme forms of punishment, and reformed the judicial system, requiring judges to pass government examinations, which in turn made them salaried officials and government servants. In legal matters, Frederick believed that the king should exercise a hands-off policy. “In the courts the law should speak and the ruler must be silent,” he wrote. “The law alone must rule.” The new system guaranteed property rights and thus laid a more secure foundation for economic development.

Although strong remnants of the feudal system continued to exist, especially in the eastern provinces,  Frederick opened the country to capital investment by fostering new industries, such as textiles. He freed the new industries from medieval guild regulations and protected them by tariffs. Frederick’s policy was intended to liberate the Prussian economy from a primarily agrarian base. He opened up the Oder River and removed obstacles to shipping, began a uniform customs system, and built canals to serve Berlin.

Frederick opened the country to capital investment by fostering new industries, such as textiles. He freed the new industries from medieval guild regulations and protected them by tariffs. Frederick’s policy was intended to liberate the Prussian economy from a primarily agrarian base. He opened up the Oder River and removed obstacles to shipping, began a uniform customs system, and built canals to serve Berlin.

Frederick also improved agricultural methods by introducing the English system of crop rotation and advocating new crops, such as potatoes. He created incentives to stimulate migration within Prussia, so that sparsely settled areas could become more populated. He created 900 new villages and lured an estimated 300,000 immigrants from neighboring principalities, especially people with technical skills or capital to invest.

In all his efforts, Frederick’s primary goal was to strengthen the state, for he believed that without a stable and unshakable government, peace and prosperity would never flourish. In his terms, “the consolidation of the authority of the state and the increase of its power” were paramount. The powers and responsibilities which are commonplace today in the modern state were, before Frederick’s time, still philosophical dreams. In the Prussia of Frederick the Great, they became reality.

Refinements

In spite of his “farewell to pleasure” that he wrote to Voltaire on his ascension to the throne, Frederick managed to maintain a rigorous daily schedule that allowed ample time for his intellectual and artistic pursuits. He drew up architectural plans for the famous palace of Sans Souci at Potsdam and turned that court into what Voltaire, a long-term resident there, would characterize as “Sparta in the morning, Athens in the afternoon!”

In a court devoid of women’s influence, Frederick would entertain his “Spartan” comrades at lunch so that he could discuss matters of warfare and diplomacy and indulge his need for horseplay. For dinner, he invited the “Athenians,” who engaged in stimulating conversation about art, philosophy, science and played music.

An unrelenting Francophile (French was his primary language; he spoke German with difficulty),  Frederick could not appreciate the reawakening of German culture during his lifetime. Significantly, when he reestablished the Academy of Sciences, he appointed a French president. He found his own countrymen pedantic and backward and considered the German intellectual life of Goethe, Herder, and Lessing far inferior to the products of the French Enlightenment.

Frederick could not appreciate the reawakening of German culture during his lifetime. Significantly, when he reestablished the Academy of Sciences, he appointed a French president. He found his own countrymen pedantic and backward and considered the German intellectual life of Goethe, Herder, and Lessing far inferior to the products of the French Enlightenment.

And yet he himself became a mythic figure, a symbol of Germanic virtues who would be hailed in literature, poetry, and popular song, an inspiration to both the elite and the common folk in his own and succeeding generations.

The fact that German culture had the seed of greatness, however, was not lost on him. He firmly believed that someday enlightened German thought and culture would take their rightful place along with other European traditions, especially after he established secure borders and a strong, centralized government, without which culture could not flower. “These beautiful days have not yet arrived, but they are drawing near,” he wrote. “I predict their coming; they will appear, but I shall not see them.”

Spiritual Pragmatist

As a man of the Enlightenment, Frederick believed in a rationally ordered universe. He never felt comfortable with his Protestant father’s belief in a personal, judgmental God; and as an adult he rejected theological dogma. His frame of reference was completely secular, based on rationalism and human understanding. He promoted religious toleration in the belief that “everyone must seek salvation after his own way of thinking.”

Of course, in annexing Silesia, half of whose population was Catholic, toleration was also a political necessity.  He invited French Jesuits to Silesia to counteract the anti-Prussian influence of Silesian monks, thus giving the Jesuits a needed refuge during the years when the order was suppressed by the Vatican. And yet Frederick would have no part of the antireligious extremism so popular in France.

He invited French Jesuits to Silesia to counteract the anti-Prussian influence of Silesian monks, thus giving the Jesuits a needed refuge during the years when the order was suppressed by the Vatican. And yet Frederick would have no part of the antireligious extremism so popular in France.

Frederick’s sense of the divine order was practical and personal. During a critical period in the Seven Years’ War, he wrote, “I save myself by looking at the world as a whole, as though from a distant planet. Then everything appears unbelievably small to me, and I pity my enemies who take so much trouble over such insignificant things.”

Personal Limits

A life structured around a rigorous sense of duty aged the monarch. He looked old before his time. As his friends died or were killed in war, he grew lonely and more isolated. In his later years, he was afflicted with asthma, dropsy, gout, and abscesses on his ear and leg.

And yet, even in his last days, he stuck to his self-imposed schedule: filling military vacancies, ordering new books for his library, studying reports from his ministers, selecting a new ambassador, ordering sheep from Spain.

In 1785, the young Lafayette visited the venerable monarch and military genius in Berlin.  The Frenchman wrote to General Washington in America: “I could not help being struck by that dress and appearance of an old, broken, dirty Corporal, covered all over with Spanish snuff, with his head almost leaning on one shoulder, and fingers quite distorted by the gout. But what surprised me much more is the fire and sometimes the softness of the most beautiful eyes I ever saw, which give as charming an expression to his physiognomy as he can take a rough and threatening one at the head of his troops.”

The Frenchman wrote to General Washington in America: “I could not help being struck by that dress and appearance of an old, broken, dirty Corporal, covered all over with Spanish snuff, with his head almost leaning on one shoulder, and fingers quite distorted by the gout. But what surprised me much more is the fire and sometimes the softness of the most beautiful eyes I ever saw, which give as charming an expression to his physiognomy as he can take a rough and threatening one at the head of his troops.”

The following year, unable to breathe, feverish and coughing, Frederick died at the age of 74.

Given what we understand today of the complexities of human nature, it is arguably certain that this bigger-than-life character allowed himself to feel and express authentic affections, from time to time, with other men who attended to his court. History and its interpreters like to downplay homosexual romance and love among well-known figures, but Frederick the Great’s inherent nature cannot be denied. He was one of the great archetypal leaders who shaped western civilization: courageous in his worldly efforts, enlightened in his thoughts, aesthetic in his soul and homosexual in his love. Surely another ‘man for all seasons’.

Also see on this site:

Gay Berlin Stories

Gay Germany News & Reports 2000 to present

Gay Berlin Photo Galleries