Sydney has an energy as vibrant as any world-class city and the LGBT gay energy is equally vital as life moves along the famous Oxford Street lined with its gay cafes, clubs, bars, discos, fashion shops, organizations and restaurants (including Betty’s Soup Kitchen).

Sydney has an energy as vibrant as any world-class city and the LGBT gay energy is equally vital as life moves along the famous Oxford Street lined with its gay cafes, clubs, bars, discos, fashion shops, organizations and restaurants (including Betty’s Soup Kitchen).

The popular LGBT venues are easy to find in this city but the organizations are less visible as each goes about its purposes for celebration (Mardi Gras gay parade and festival), for sport (Wett Ones, FrontRunners among others) for health (ACON, the main HIV/AIDS agency), and for business (SGLBA).

This trip (my third) I was not looking to do another sprawling survey about the widespread gay scene in Sydney and elsewhere; it’s still widespread and still very gay. Rather this was a more focused visit to the quieter and no less busy side of gay life as seen through the eyes of the AIDS Council of New South Wales.

ACON (AIDS Council of New South Wales)

ACON is a major presence in the Sydney scene. On their website it says. “Australia’s largest community-based LGBT health and HIV/AIDS organization.” It offers HIV educational prevention programs for people most at risk of HIV transmission: gay men, sex workers and people who inject drugs. Also included in the programs are people living with HIV, their families and care-givers. ACON is also involved in policy-making and rights advocacy on behalf of its clientele.

It’s a huge challenge and ACON’s response has been high visibility and extensive outreach with their many programs, publications, diverse staff and wide ranging services.

Within a day after arrival I attended three ACON-sponsored events: a forum with the renown gay Crown Prince Manvendra from India on a visit to Australia to describe his own HIV/AIDS education and prevention work involving Lakshya Trust. (photo left)

Within a day after arrival I attended three ACON-sponsored events: a forum with the renown gay Crown Prince Manvendra from India on a visit to Australia to describe his own HIV/AIDS education and prevention work involving Lakshya Trust. (photo left)

Next day, a lunch and ACON office tour with Solomon Wong of ACON’s Gay Asian Men’s Health Promotion Program.

Later that evening I saw the inauguration of new ACON-supported Alzheimer’s program for gay elders launched by the Hon. Michael Kirby, the openly  gay former Australian High Court Justice. (photo right)

gay former Australian High Court Justice. (photo right)

Impressive

It’s hard not to be impressed with the energy here in Sydney, an energy that derives from the frisson of different cultures, races, ages, sexual diversities, free enterprise and tourists pouring into the city daily to gawk at the opera house, climb the bridge, cruise the beaches, wander the botanical gardens, marvel at Darling Harbor or soak up the creativity in the Art Museum—among a hundred other things to see and do in this tall and wide city of four million by the harbor (founded originally in 1787 as a penal colony to relieve England’s overcrowded jails—most guilty of petty misdemeanors).

The energy is everywhere. The hookers on Darlinghurst Road, the gay and straight flashing discos, the bustle of upscale shoppers at Queen Victoria Building, the density of youthful backpackers from everywhere (they can legally work here short-term), the beer-guzzling soccer fans, boutique restaurants and San Francisco’s visiting Ballet Trocadero dancing through town on a world tour.

The streets tee m with people from everywhere else—Nepal, Slovakia, Ireland, Holland, Jordan, Norway, Arabia, South Africa– and no where here (the land of the Aborigines beyond dreaming).

m with people from everywhere else—Nepal, Slovakia, Ireland, Holland, Jordan, Norway, Arabia, South Africa– and no where here (the land of the Aborigines beyond dreaming).

In King’s Cross (we stayed at the charming modest Springfield Lodge) the Fitzroy Gardens space offers a weekend ‘farmers market’ with food stalls and produce as well as a games area for kids and parents. I sat close to two gays dads playing backgammon with their son while another clutch of gay friends greeted each other with kisses and two lesbians strolled by hand in hand.

Later, while using the free internet service at the Kings Crossing branch of the public library, I glanced over the magazines racks to see, along with Vanity Fair, Time, Archtectural Digest, Home & Garden a copy of the very gay, very spicy DNA magazine with it’s full-page crotch shots of buff boys in fashion underwear. (photo left) . Welcome to Sydney’s ‘edge’ where diversity and fashion meet prostitutes and dope smoking backpackers, where scrubbed catholic parishioners going to evensong brush past Harley homos on their way to a watering hole in the same part of the city.

. Welcome to Sydney’s ‘edge’ where diversity and fashion meet prostitutes and dope smoking backpackers, where scrubbed catholic parishioners going to evensong brush past Harley homos on their way to a watering hole in the same part of the city.

Up Close

Sydney has half a dozen legal sex clubs each with a different milieu. In the 357 Sauna, in the central business district with shoppers and soccer moms hurrying past, an ACON brochure is on offer titled ‘When You’re Hot You’re Hot’. It’s unusual in that it was created specifically for that type of venue. It is a direct and to-the-point comprehensive message for newbies about sex clubs and what to expect and how to act (safely).

Another brochure there is ‘Real Time: the truth about fucking without condoms’ put out by AFAO (Australian Federation of AIDS Organizations). It too is direct and appropriately no-nonsense. To reach a ‘jaded’ target population the language of safe-sex has to be edgy as well.

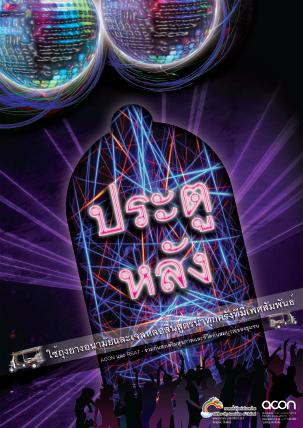

During my visit there was a special outreach program being mounted to reach the many workers and visitors from Thailand in Sydney. Printed in the Thai language, the ‘up-ya-bum’ ad campaign was running in the gay media. (photo left)

Such proactive programs impress a visitor with a positive sense about Sydney as a world-class act that validates human sexuality while protecting it at the same time.

Most Sydney sex venues are recognized by the AIDS Council of New South Wales (ACON) for complying with their safety code practice to provide free condoms, lube, adequate lighting, safe injecting disposal equipment, and free safe sex information.

Solomon Wong from ACON

My look at Sydney through the eyes of ACON started with an Oxford Street cafe conversation with Solomon Wong, ACON’s ‘social mom’ who organizes and publicizes the popular and extensive social activities for ACON’s Gay Asian Program that attracts many ethnic people from all over Asia–including Solomon (photo right) whose family is Chinese and his boyfriend who is Taiwanese.

Solomon’s described ACON as the largest of Australia’s eight states’ members of the national umbrella organization AFAO (Australian Federation of AIDS Organizations). This countrywide federation provides “leadership, coordination and support to the Australian national policy, advocacy and health promotion response to HIV/AIDS”. Australia is an enormous country with major cities both close and very far from each other. AFAO ensures continuity of programs, funding, outreach and health care across the thousand of miles of the territory.

Since Sydney is by far the largest metropolitan area with the largest population of HIV affected people it is challenged to provide adequate services to its very diverse ethnic and majority communities. After our a chat about discrimination among gay ethnic groups, which still persists,  we went with Solomon to visit ACON’s offices in central city. This was no backroom deal; it’s in a major office block on the ground floor and impressively stylish.

we went with Solomon to visit ACON’s offices in central city. This was no backroom deal; it’s in a major office block on the ground floor and impressively stylish.

The place was loaded with information brochures and leaflets and notices, a well-stocked library and numerous social services at the ready. As I walked around I noticed a feeble older client slowly make his way to an office escorted by a compassionate counselor.

Gay Aborgines

Needless to say, ACON outreaches to gay Aborigines although they are a small and hesitant community. I asked ACON CEO Mark Orr (photo right) how his organization accesses them? Do they have a gay ‘community’. Are lesbian Aborigines receptive to their programs? What is the Aborigine attitude toward homosexuality?

His reply: “The situation in Australia with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is a sad one and much could be written about that.

Nevertheless, ACON has an Aboriginal project. (Said Orr, “we use the word Aboriginal as a stand-alone term in NSW since the land we are on is Aboriginal land–not Torres Strait Islander land–staffed by people from the Aboriginal community.”)

They work with both LGBT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in relation to HIV as well as more general health promotion. There is a Reference Group made up of Aboriginal people who advise ACON on the work in those communities.

“As a symbolic way of welcoming Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, ACON’s building flies the Aboriginal flag. As well, the website acknowledges the “traditional owners” of the land across NSW to remind people that “we are on Aboriginal land and we acknowledge the Elders and those natives visiting this website”.

Some of the work in these communities is outlined on ACON’s website:

http://www.acon.org.au/communities/aboriginal and also in their newsletter:

http://www.acon.org.au/sites/default/files/Newsletter-June09-final.pdf

Booklet for Aborigines

An important part of their mission is nurturing and validating alienated Indigenous LGBT young people who feel they belong nowhere as a result of being homosexual and Aboriginal/Torres Islander. Toward the goal of inclusion ACON has produced a resource booklet: However You Wanna See Me, I’m Just Me: Stories from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Gay Men, Lesbians and Sistergirls

The stories in this booklet tell of ‘injured souls’ finding support from friends, peers and organizations. They give touching examples of how they have found strength and have overcome obstacles that makes the community safer and more accepting for everyone.

Here are three stories (out of twelve) about being Aborginal and gay, experiencing abuse and feeling vulnerable. All stories are available in the booklet.

The first story from a young adult lesbian Aboriginal woman: (page 9)

“We have to make people in the community realize; you’re related to us mob (Aboriginals). You’re related. You’ve got lesbians in the family. You’ve got gay men in the family. You’ve got transgender people, sistergirls, in your family. You’re related.

“Because we’re all part of a community and feeling isolated from our own family and community can have a terrible impact on our lives. I’ve had family members say hurtful things and I felt quite isolated at times. I suffered anxiety and depression.

“I still sometimes get anxious or nauseous, sick in the stomach, thinking that something’s gonna be said to me or I’m gonna be blamed for something because of my sexuality You can draw on your inner strength as well, you go into survival mode. I’m careful with people about how much I expose about myself and to who. Because when you’re younger, sometimes you don’t think before you speak or act.

“As you get older you find out that there is support around – other friends, other indigenous lesbian women. That’s what’s helped me through. I look forward to the future. I look forward to being an older lesbian in the community and being able to share my experiences and support younger people. “I’ve gotten through it with support of other people that weren’t discriminatory.”

An Indigenous lesbian mother relayed this sad story: (page 13)

“The worst experience was having a group of teenaged boys urinate at our front door and threaten to kill us.Every time they walked past our house they’d expose themselves and yell out “come suck my c*ck ya f**king lezos”.

“We had to take out an apprehended violence order but it wasn’t worth the paper it was written on. They continued with the abuse and threats. We lived in a small village in rural New South Wales state. My partner had lived there for many years. We constantly worried about our children’s safety as well as our dog.

“It all got too much for us and we moved to the coast. I felt absolute rage at first. Then humiliation and despair; our self esteem was non-existent, and then fear set in. We then began to question ourselves, wondering if we had displayed any form of affection in public that may have provoked it.

“I’m careful in public and at home we keep all displays of affection indoors. My partner is more fearful than me about history repeating itself, she won’t even kiss goodbye on the cheek in the front yard. It’s therapeutic to be with like-minded individuals sharing our experiences. It puts things in perspective; it’s bizarre how we have learnt to laugh about some of our most hideous experiences.”

An Indigenous man had this to say about his experiences: (page 19)

“Living in a rural community has presented a daily challenge. I am confronted by homophobia weekly, either being screamed at by people in a passing car, snickered at or pointed at by men or women.

“At times it has hurt me and also made me fear for my own physical safety. It outlined to me that homosexuality, at least in my large rural community, is barely tolerated. At times I feel I am virtually invisible and overshadowed by my sexuality.

“I am not gay, I am also gay, there are other aspects to me. I have spent long periods of time justifying people’s homophobic reactions. I have concluded that their attitude and behaviour is based on fear, ignorance and at times a true hatred for difference.

“I have become more consciously aware of the abuse. I have also advocated for equality in different forums. I have just survived it. I have come through those times by having friends to confide in, who allow me the opportunity to explore the stupidity of hatred. If I am going out to the pub, being in a larger group of friends has been helpful; there is a feeling of safety in numbers. Unfortunately I’ve also changed and shaped my social behaviour and gestures so as to fit in and not to attract un-needed attention.”

An Indigenous lesbian mother relayed this sad story: (page 13)

“The worst experience was having a group of teenaged boys urinate at our front door and threaten to kill us.Every time they walked past our house they’d expose themselves and yell out “come suck my c*ck ya f**king lezos”.

“We had to take out an apprehended violence order but it wasn’t worth the paper it was written on. They continued with the abuse and threats. We lived in a small village in rural New South Wales state. My partner had lived there for many years. We constantly worried about our children’s safety as well as our dog.

“It all got too much for us and we moved to the coast. I felt absolute rage  at first. Then humiliation and despair; our self esteem was non-existent, and then fear set in. We then began to question ourselves, wondering if we had displayed any form of affection in public that may have provoked it.

at first. Then humiliation and despair; our self esteem was non-existent, and then fear set in. We then began to question ourselves, wondering if we had displayed any form of affection in public that may have provoked it.

“I’m careful in public and at home we keep all displays of affection indoors. My partner is more fearful than me about history repeating itself, she won’t even kiss goodbye on the cheek in the front yard. It’s therapeutic to be with like-minded individuals sharing our experiences. It puts things in perspective; it’s bizarre how we have learnt to laugh about some of our most hideous experiences.”

Reparations

ACON staff and volunteers consist of various minority and majority members who each have their own stories of being racially or sexually different as youth and as adults. Developing indigenous-specific services, outreach and literature is their way of not just offering health and social care but is a respectful gesture toward reparation for the historic degradation of the Aboriginal culture at the hands of the early white settlers and their descendants.

(See the film ‘Rabbit-Proof Fence’ based on the book ‘Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence’ by Doris Pilkington Garimara, plus the documentary. It follows the lives of two kidnapped young mixed-race girls trying to escape white authorities and return to their native homeland.)

As a result, the level of sensitivity among the ACON workers is extraordinarily high and it’s reflected in their outreach to minority individuals and groups.

Solomon said one of the most difficult groups to access are Muslim LGBT people who usually have multiple layers of self-protection and invisibility; being gay, Muslim, foreign and often dark-skinned they are particularly vulnerable to bias and discrimination and, thus, much in need of support from other gay people.

But many are reticent to come to ACON’s activities and premises out of fear of exposure, so recruited Muslim outreach staff go to them in focus neighborhoods to discretely offer support and advice where possible, using HIV prevention as an entree issue. Secretive networks are an important ‘system’ in this sensitive work.

Finally

This has been a story about vibrant Sydney but on a smaller more focused scale. The ‘scene’ action with its music and lights may be what’s most noticeable but it is not home for most of the city’s LGBT citizens whose lives are defined more by work, partnership, parenthood, health and ethnicity–and some day, gay marriage.

Although they are connected to the larger community of the city and country in the manner of their sexual attraction and affection, life for most happens at home and in their minds. That’s where ACON tries to meet their needs.

Also see:

Gay Australia News & Reports 2000 to present

Gay Australia Photo Galleries