Gallery introduction by David Laskin, New York Times, September 30, 2007 and Richard Ammon, GlobalGayz.com, 2010

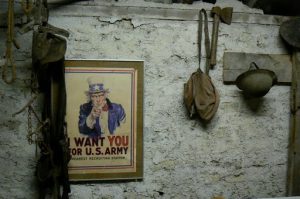

In the tiny village of Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, adjacent to the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery and the Montfaucon Monument, a dedicated Dutch couple, Bridget and Jean-Paul de Vries, have opened the intirguing 14-18 Museum to display their extraordinary collection of World War I artifacts. Within 5 kms around Romagne, the deVries have turned up more than 30,000 objects from the Meuse-Argonne Offensive of Sept-Nov 1918: machine guns, bayonets, helmets, ammunition, gas canisters, mess tins, entrenching tools, ink pots, cigarette lighters, boots, wine bottles, gas masks, bunk beds dog tags, etc.

The souvenirs are hung and heaped in dusty piles and wall displays and in display cases on two floors of a spacious old barn attached to a cafe. Walking slowly around has a visceral impact. The de Vries have left the aged rust and scratches and mud on the objects he has gathered, both by himself and by local farmers during plowing season. Everything can be touched; the feel of hand grenade in your palm is unsettling.

In Erich Maria Remarque’s classic World War I novel “All Quiet on the Western Front” he describes how German soldiers came to prefer shovels to bayonets for hand-to-hand comba; rather than stab the enemy, they used the sharpened edge of a shovel to bash in his skull. When I asked Mr. de Vries if he thought there was anything to this, he promptly fetched me a helmet with two gashed dents on the top and a bullet hole in the front, right where the forehead would have been. “We know what happened to the guy who wore this,” he said grimly.

The most daunting items were the helmets with bullet holes. Of the 9.7 million soldiers who died fighting the war that ended nothing, resolved nothing and made the world safe for nothing but more war, for each helmet an individual died with such a steel bowl on thhis head. Standing there wearing it, I (the Times reporter) had the usual pieties about waste and shame running through my brain. But what I felt in my gut was pure, inexpressible pity. For myself, Richard Ammon, imagining one of these belonging to my great uncle was very sad.