By John Champagne

Gay and Lesbian Review

May-June 2009

The Avenue Habib Bourgiba is downtown Tunis’s main thoroughfare. Built by the French colonizers as a version of the Champs Élysées and named after Tunisia’s first president, it stretches virtually from the bay of Tunis to the entrance to the medina, the ancient city. While the avenue is divided by a wide promenade full of trees that provide welcome shade in the hot summer months, most pedestrians prefer to stroll along the sidewalks on either side of the street. Lined with restaurants, banks, movie theaters, high-rise hotels, and shops, these sidewalks offer a perfect vista for people-watching.

Day-tripping European tourists from cruise ships, dressed scandalously by Tunisian standards in shorts, tank tops, and flip-flops; slender and handsome Tunisian teenage boys, their arms draped around one another’s shoulders or waists; middle-aged women in colorful headscarves holding hands with their jean-clad daughters; members of the large Tunisian military bureaucracy: police, traffic cops, embassy guards, soldiers; visitors from nearby Algeria and Libya or wealthier and more distant Egypt or Dubai—all can be spotted taking an afternoon stroll along the sidewalks of the avenue.

I learned early on in my tenure as a visiting professor of English at a Tunisian university that the best place from which to enjoy the crowd is a seat on the terrace of one of the many cafés. Cafés are among the only public places where men and women, Tunisians and tourists, all gather and mingle. But because Tunisia is a Muslim country, and only foreigners are allowed to drink alcohol on a terrace.

Most cafés are gender-segregated, the majority being places where local men go to drink coffee, smoke tobacco from a hookah, play cards, and network—a vitally important activity in a country where jobs can be scarce. But because Habib Bourgiba is prime real estate, its cafés tend to be welcoming to both men and women.

At a café on the avenue, for two dinars or so (equivalent to $1.60) one can wile away a whole afternoon reading a newspaper, sipping a Coke, and perusing the passing crowd as if one were a local. Given the history of North Africa, Tunisians do not have a single, identifiable “look,” and some of my fair-haired, blue-eyed students—people of Berber extraction—are sometimes mistaken by other Tunisians for Westerners. (The Berber presence predates the Arab conquest of North Africa.)

In deference to my hosts and as an attempt to “pass,” I never drank alcohol in public, just as I never wore shorts or tee shirts, and I learned a few words of Tunisian Arabic. However, I was never mistaken for a local. Something about my appearance—or perhaps it was the fact that I drank “cola-light”—always gave me away, though generally people assumed I was French rather than American.

In deference to my hosts and as an attempt to “pass,” I never drank alcohol in public, just as I never wore shorts or tee shirts, and I learned a few words of Tunisian Arabic. However, I was never mistaken for a local. Something about my appearance—or perhaps it was the fact that I drank “cola-light”—always gave me away, though generally people assumed I was French rather than American.

What I almost never saw from my seat at my favorite haunt—the Café de Paris, chosen because, not attached to a hotel, it always attracted more Tunisians than tourists—were any signs of a visible, easily identifiable gay or lesbian culture. While the gay visitor in particular might be thrown initially by the ways in which two men or two women openly display their physical affection—whenever we would cross the avenue together, for example, my friend Hsin would grab my hand to make sure that I would not be run down by one of Tunis’s notoriously reckless cab drivers—and while the sight of a man walking down the street with a jasmine blossom tucked behind his ear might (wrongly) suggest otherwise, open signs of Western-style gay identity are frowned upon if not absolutely taboo.

I found it nearly impossible to spot any Tunisian I could identify as gay. Nevertheless, same-sex desire, if not a gay identity, is certainly present in Tunisia. The ways in which it is expressed, however, are complicated and sometimes contradictory.

Historians and anthropologists have noted that, in the Mediterranean, there is a long historical tradition of sexual coupling in which an older though unmarried “active” male pursues a younger, “passive” one, a practice conditioned, perhaps, by the late age at which people marry and the resulting long period of segregation of the sexes. In some cases, this adolescent homosexual behavior is considered a stage of life that will soon be left behind, so men who continue the practice into adulthood—or, worse, who still prefer the passive role—are open to criticism, or worse. But sexual acts carried out in one’s youth do not add up to a fixed identity.

In more recent times, however, as a result of global media broadcasts via satellite television and the Internet, Tunisians are regularly exposed to Western notions of gay identity. Nearly every home in Tunisia has some kind of satellite device, jerry-rigged or otherwise. Though sometimes clumsily censored, Western shows with gay characters—like The OC or the Spanish Un Dos Tres, a Fame-style show about a performing arts school—are easily available via satellite dish, as are gay phone sex ads that made me blush.

We also sometimes forget the ways in which, even in the West, gay style is communicated through the media and “assumed” by us as we figure out how to represent ourselves to each other and to a larger heterosexual public. As Tunisians who feel same-sex desire see more Western representations of gay life, they’re likely to imitate these ways of being and acting, however constrained by the confines of an Islamic social system.

Because a visible gay identity is often seen in the Islamic world as a product of the West, it is difficult to untangle a rejection of gay identity from a rejection of the West with its profoundly different standards of public behavior and private morality. By the same token, Muslims in Tunisia and elsewhere are also aware of negative representations of Islam in the Western media. As the late Edward Said pointed out, this awareness gives rise to a defensive reaction against the West and all that it represents.

Thus, for example, young women in countries like Tunisia who might never have chosen to wear the hijab, or head scarf, are today choosing to wear the more conservative veil as a sign of their faith. In the face of Western hostility to the veil, they feel compelled to adopt this very public signifier of traditionalism. Something to consider, then, is the possibility that the tendency of our media to portray Islam in a negative light is making it harder for those Tunisians who wish to “come out” as independent women, as gay, or as otherwise nontraditional.

The fact that gay identity is built precisely upon a public acknowledgment of being gay complicates things in a society where, for example, men are so modest that they shower in their underwear at the gym, or where, until recently, heterosexual couples could not so much as hold hands in public. Not surprisingly, whatever gay life that exists takes place covertly, while the life in its more public forms is virtually nonexistent.

Homosexuality, Tunisia Style: Where the Action Is

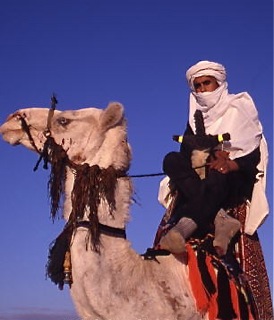

In Tunisia, the issue of gay identity is complicated by the country’s long history of European tourism, including sexual tourism. Thanks chiefly to some earlier Western travelers, young Tunisian men tend to assume that any single guy of European heritage is looking for vacation sex and is willing to pay the going rate. Many of these men might be called, in a Western expression, “gay for pay.” The fact that they’re willing to have sex with a Westerner for money does not disturb their heterosexual identity in the least—particularly if they’re going to play the active role.

The presence of hustlers on the streets and beaches of Tunisia is so prevalent and remarked-upon, including by Tunisians, that it has become the subject of a Tunisian film, Nouri Bouzid’s Bezness (1992). The film explores the life of a hustler—whose clients include both men and women—along with his fiancé, whom he expects to remain a virgin until they marry, and a visiting French photographer. The title is a kind of humorous combination of the English word “business” and French word “baiser,” slang for sexual intercourse.

The presence of hustlers on the streets and beaches of Tunisia is so prevalent and remarked-upon, including by Tunisians, that it has become the subject of a Tunisian film, Nouri Bouzid’s Bezness (1992). The film explores the life of a hustler—whose clients include both men and women—along with his fiancé, whom he expects to remain a virgin until they marry, and a visiting French photographer. The title is a kind of humorous combination of the English word “business” and French word “baiser,” slang for sexual intercourse.

The Café de Paris was largely frequented by men and had a reputation for being a place for Westerns and Tunisians to connect. I frequented the establishment because it was one of the only places in Tunisia where I could experience some semblance of a gay culture, but I had to learn to cope with the daily propositions. The pitch usually began with “Bonjour!” and progressed to a request for a coffee, ending with me either paying my check and fleeing or simply ignoring the harmless if sometimes annoying intrusion. Even when my partner came to visit me in Tunis, we still found ourselves being propositioned—as a couple. (I learned eventually not to make eye contact with any man on the street, as it could be mistaken as an invitation.)

I tried once to talk with my Tunisian students about these men who propositioned me virtually everywhere I went. Some of them laughed with embarrassment. Given the tendency of Tunisians to want to make their best impression on Western visitors—Tunisia is heavily dependent on tourist dollars—it’s not surprising that they were reluctant to talk about something that’s undoubtedly a source of shame. I was their teacher, someone whom they always treated with respect, calling me sir, wiping the dust from my chair before I sat down at my desk, giving me their seat on the tram from school.

Because Tunisia is effectively a police state run by strongman President Ben Ali, people are reluctant to discuss in public any topic that might be controversial, including one that encompasses sex, corruption, Western exploitation, and several other taboos all rolled into one. However, one young woman spoke up, insisting that I would be subjected to the same sexual advances in any big city in the U.S. I didn’t know how to respond to this claim. Perhaps, if I were in a particular neighborhood in New York or San Francisco, I might be approached by a male prostitute; but in broad daylight, at a café, within earshot of the other customers? It didn’t seem likely.

While visiting the resort city of Sousse, while walking along the beach one afternoon, I was approached by a boy who seemed no older than fourteen. Instead of simply ignoring him, this time, I scolded him (in French), saying that I was old enough to be his father. I then asked him what other Tunisians would think of me—and him—had they seen us together sitting at a café. He apologized. The absence of free speech in Tunisia is such that everyone watches and listens to everyone else discreetly but carefully, and people are especially conscious of interactions between Tunisians and Westerners.

There’s also a palpable sense that one does not want to  behave shamefully in public. How one dresses, speaks, and interacts with others is always a matter of public scrutiny. Tunisians are very proud of their multicultural heritage. Berbers, Greeks, Carthaginians, Jews, Romans, Byzantine Christians, Arabs, Italians, the French—all settled at various times in Tunisia. Tunisians are sometimes accused by other Arabs of thinking they’re more European than the rest of the Islamic world. Consequently, to be publicly humiliated in front of a Westerner constitutes a special loss of face.

behave shamefully in public. How one dresses, speaks, and interacts with others is always a matter of public scrutiny. Tunisians are very proud of their multicultural heritage. Berbers, Greeks, Carthaginians, Jews, Romans, Byzantine Christians, Arabs, Italians, the French—all settled at various times in Tunisia. Tunisians are sometimes accused by other Arabs of thinking they’re more European than the rest of the Islamic world. Consequently, to be publicly humiliated in front of a Westerner constitutes a special loss of face.

One of my colleagues at the university, now a grandfather, once confided to me that, in his youth and even young adulthood, he had in fact had sex with other men—even Jews! (Afraid of where the conversation might lead, I never disclosed to him my gay identity.) To my colleague, as he further disclosed, a beautiful body is a beautiful body, whether it belonged to a man or a woman, and availing one’s self of sensual pleasure with a person of either sex was as natural as eating Tunisia’s succulent figs, oranges, dates, and pomegranates.

In addition, I also had two Tunisian friends who self-identified as gay. One had been educated in the U.S.; the other was his sometime lover. Hichem (not his real name), a man who looks far younger than his fifty years, is married to a woman, a famous Tunisian actress, whom I believe is a lesbian. Hichem confided to me many details of his sex life—often, hilarious stories about young men who claimed to be virgins but who seemed to not have any of the usual physical difficulties generally associated with one’s “first time.”

His homosexuality, along with his antipathy for religion of any kind and his awareness of the many ironies of his role as a university professor in a police state, had left him, if not exactly jaded, at least world-weary from a lifetime of knowing, but never being able to say out loud, that the emperor has no clothes. At the same time, he was one of the kindest, funniest, most generous men I’ve ever known, someone who wanted nothing from me but friendship.

Hichem’s sometime lover Nizar was also a good friend, a sweet boy who wanted nothing more than a monogamous relationship with his wandering partner and who often joked with me in English. When the two of us took a walk down the avenue, however, Nizar noticed the way people looked at us—as if I was paying for his company. Sometimes, vendors would even try, in Arabic, to enlist his aid in selling me something at a price far lower than what a non-tourist would pay.

While living in Tunisia, I had a visit from a Parisian friend, Jacques, who had no qualms about renting hustlers. As a result of his visit, I learned of another café on the avenue, one even more active than the Café de Paris. I also learned that there are hotels that rent by the hour, where the management is fully aware of what’s going on. At this café, where Jacques me t his rent boy, I saw what I would identify as the only visible signs of a gay identity that I saw: some young men conducting surveys about safer sex practices. I was amazed that, as repressive as the Tunisian government is, and as far into denial of its underground economies, apparently someone in public health had authorized this survey. (Such a survey would never have been distributed, had it not been approved by someone in power.)

t his rent boy, I saw what I would identify as the only visible signs of a gay identity that I saw: some young men conducting surveys about safer sex practices. I was amazed that, as repressive as the Tunisian government is, and as far into denial of its underground economies, apparently someone in public health had authorized this survey. (Such a survey would never have been distributed, had it not been approved by someone in power.)

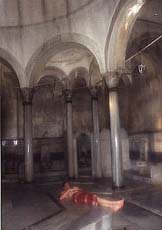

Via Jacques, I also learned of a hammam that caters primarily to men looking for sex with other men. In Muslim cultures, where ritual cleanliness is practiced and there are strict rules related to personal hygiene, hammams or steam baths are both public bathing facilities and places for people of the same sex to relax and socialize. Located just inside the medina, this particular hammam was apparently an open secret tolerated by the Tunisian police, undoubtedly because it catered to tourists and most likely paid bribes. Jacques told me that during his visit, one of the customers—a non-Tunisian Arab—openly bragged of wanting sex with other men. Others, including the staff, were more discrete, offering massages. As Tunisians always wear a swimming suit or underwear at the hammam, I had a hard time imagining how or where the sex actually managed to take place.

One of my female Tunisian colleagues, someone to whom I had never come out, sent me an e-mail recently. She had read an essay of mine on-line, a story I had written about a previous trip to Tunisia—one during which I was hustled by a Tunisian who left me both broken-hearted and several hundred dollars poorer. She wanted to tell me that she found my essay moving and that my being gay was not an issue for her. But she warned, “I also wanted to tell you to be careful to raise gay issues in Arab countries. We do have gays and lesbians just like in any other society, but it’s a very closed circle of people and they do everything to hide it and keep it secret.”

She was particularly concerned that when I return for a visit I not become a victim of violence, as foreign gays can be targeted. (Every once in a while you read in the French press of a tryst gone bad, usually involving a Westerner who is at first very generous with his money but eventually stops paying.) I was really touched by her willingness to discuss what to even a highly intelligent and educated woman must be a difficult matter, given the realities of Tunisian society. One of the most difficult things to covey to my American friends is the complexity of Tunisian culture. My trips to North Afric a have caused me to recognize that we cannot assume that our way of inhabiting our sexuality is shared by people of different cultures, and that it is not always necessary to conclude that “different” means either “worse” or “better.”

a have caused me to recognize that we cannot assume that our way of inhabiting our sexuality is shared by people of different cultures, and that it is not always necessary to conclude that “different” means either “worse” or “better.”