By staff writers © Afrol News

http://www.afrol.com/features/

Changing Times

In colonial times, Senegal’s metropolis Dakar was famous for its open and tolerated homosexual prostitution market, and as late as in the 1970s, as many as 17 percent of Senegalese men admitted having had homosexual experiences.

Now, Dakar is West Africa’s centre of gay oppression. The government of Senegal has made it clear that homosexuality is un-African. Since 1965, same-sex activity has been punishable by up to five years imprisonment, but only during the last five years, Dakar’s former visible gay community has had to go underground, risking punishment.

History: Homosexuality is Not Un-African

Dakar’s gay history is the best example demonstrating that homosexuality is not un-African. Indeed, homosexuality has been a visible and well-known part of Wolof traditions, and only moralist opinions of the colonialists, later adopted by an increasingly dominant Muslim clergy, led to the suppression of this culture.

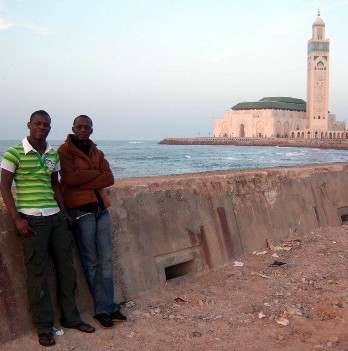

(photo right, gay couple Baba and Baidy had to flee Senegal after a local newspaper printed their photo)

The old Wolof name for homosexual men is gor-digen, or men-women. Armand Marie Corre, a French navy doctor stationed in Senegal in the 1870s, writes how he met many locals “with feminine dress and demeanour, who he was told, made their living from prostitution.” Dr Corre referred to the Wolofs’ appetite for “morbid eroticism” in his critical report; the oldest known written records of homosexuality in Senegal.

In the 1930s, European reports about the exotic gor-digen increase in numbers, reflecting their visibility in the streets of Dakar. Traveller Geoffrey Gorer reports the men-women are “a common sight” and that “they do their best to deserve the epithet by their mannerisms, their dress and their make-up; some even dress their hair like women.”

Mr Gorer interestingly notes that these openly gay men “do not suffer in any way socially, though the Mohammedans refuse them religious burial.” French colonial authorities, although not trying to stop same-sex prostitution, however claimed to be bothered by the practice but blamed it on “Muslim culture” – a widely held misunderstanding among Europeans at the time.

British historian Michael Crowder, travelling West Africa in the 1950s, was also puzzled by the visibility of the gor-digen and male prostitution in Dakar. Even on Place Prôtet – which is now Dakar’s prestigious centre square Place de l’Indépendence – young Senegalese males waited to be picked up by elder men.

“The elders and faithful Muslims condemn men for this,” Mr Crowder noted, thus documenting a slowly growing intolerance towards homosexuality from the local clergy. “But it is typical of African tolerance that they [the male prostitutes] are left very much alone by the rest of the people,” Mr Crowder however added.

British traveller Michael Davidson described Dakar in 1949 as “the ‘gay’ city of West Africa.” When he returned nine years later, “Dakar was gayer than ever” and nobody did have to shy about his homosexuality in the city. And by 1958, he recalls, homosexuality was not confined to the French dominated centre of Dakar, but to the nightlife in the “native quarters” and shantytowns surrounding the capital.

Mr Davidson reports about brothels and nightclubs dominated by the gor-digen. A suburban club “was full of adolescent Africans in drag. … Most of them were indeed in girls’ clothes: some in European, some wearing the elaborate headdress of the West African mode. … They danced together. They camped around like a pride of prima donnas. They came to our table and drank lots of beer with us,” he recalls.

Raymond Schenkel was the first to present scientific research about the sexuality of the Senegalese in 1971. A non-random survey of Senegalese made by the researcher revealed that 17.6 percent of male respondents and even 44.4 percent of females said they had had homosexual experiences. The researcher also noted the big visibility of homosexuality in Dakar.

Dakar remained West Africa’s gay capital during the 1970s and 1980s. But attitudes started changing during the 1980s. Dutch anthropologist Niels Teunis in 1990 found that Dakar men engaging with men were changing their identity. While many still used the Wolof term gor-digen, several men now referred to themselves as “homosexuèles” in French.

A connection between the Wolof gor-digen tradition and the international notion of “homosexuality” – a much wider definition often excluding the option of marrying someone of the opposite gender – was slowly being established. Picked up by government and the clergy, influenced by homphobic trends in Africa, this connection should lead to the destruction of the gor-digen culture.

Modern Times

At the beginning of this milennium, homosexuality was becoming more taboo and less visible in Dakar. But still in the mid-2000s, gay meeting points were well known to Dakar inhabitants and gay men relatively openly could pick up equally oriented men in terrasses of the famous beach promenade Corniche Ouest in the centre at plain daylight. Most parties, however, started going underground.

Around 2005, Dakar had become a more conservative city at large. While the city centre earlier had a saga-like nightlife with live music and heavy alcohol consumption, Dakar now is more in line with other Muslim cities. Nightlife, alcohol and sex during the last decade have been widely sent to the domain of taboos. Homosexuality has turned into the greatest taboo.

And during the past two years, government got tough on homosexuals. Anti-gay rhetoric in the media and by politicians against individuals believed to be gay or lesbian sharply increased. Suddenly in 2008, the 1965 law punishing same-sex activities was rediscovered, with the arrests of more than 50 people and trials of at least 16 individuals until now.

Today

In February 2008, publication of photographs from a same-sex commitment ceremony set off a wave of arrests and an anti-gay media frenzy and sent dozens of gay men into exile. In December 2008, police raided an HIV training hosted by a local AIDS organisation suspected of aiding gay men.

In November 2009, Safinatoul Amal, an organisation charged with the spiritual protection of the town of Touba, raided a man’s home and arrested him for forming a “network of homosexuals.” In December, 24 men were arrested at a private home. The arrests were accompanied by sensational media coverage, strong homophobic statements from religious and political leaders, and violence — including physical attacks and the exhumation and desecration of the bodies of deceased people suspected of being gay.

By now, the Wolof culture of the gor-digen is suppressed and homosexuality is branded un-African. Together with neighboring The Gambia, Senegal has turned into the centre of homophobia in West Africa. Dakar, the refuge for the gor-digen of the entire region, is now a source of gay refugees.

Dakar’s “typical African tolerance”, noted by Mr Crowder 60 years ago, has been replaced by typical post-colonial intolerance.

Recommended further reading about the history of homosexuality in Africa: “Boy-wives and Female Husbands” edited by Stephen O Murray & Will Roscoe, New York 1998. ISBN 0-312-21216-X. The book also includes a resume of Mr Davidson’s tales from Dakar from 1958.