Compiled by Richard Ammon

GlobalGayz.com

February 2012

Introduction

Same-sex sexual activity is technically legal, most likely only because it is not mentioned in the criminal statutes of Niger because most authorities do not think it exists in their country. Of course, there are no anti-discrimination laws for LGBT citizens and no ‘community’. The U.S. Department of State’s 2010 Human Rights Report found that “there were no known organizations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender persons and no reports of violence against individuals based on their sexual orientation or gender identity. However, gay persons experienced societal discrimination.”

(http://paei.state.gov/documents/organization/160137.pdf)

(1)

A Different Kind of LGBT Life in Niger

From: www.rainbowfund.org

In contrast to the usual stories of LGBT persecution and homophobia, here is a different sort of gay presence in Niger: a charity engaged in humanitarian efforts to relieve suffering.

(photo: Niger women; credit galenfrysinger.com)

Niger is an impoverished, landlocked country in West Africa, currently ranking sixth in the world for infant mortality, according to the CIA World Factbook. Due to a recent drought that destroyed the previous year’s crops, combined with the swarms of locusts that ensued, the sub-Saharan country of Niger is facing catastrophic countrywide famine, according to the United Nations. Crop loss coupled with a recent spike in population growth have caused about one fourth of Niger’s population of over 3 million people to suffer starvation. Another million people will soon reach starvation if this situation continues.

UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan planned a trip to Niger August 23, 2011 to garner international support of the relief efforts in Niger, along with meeting with Niger’s president, Mamadou Tandja, to address this issue as well as to discuss the country’s future of peace, security, and development. The UN issued an appeal for relief to the nations of the world that was met with a moderate response; global private donations totaled around $3 billion, and the United States contributed about $13 million, but millions more are needed to get Niger stabilized. Part of the problem in raising enough funds to stabilize Niger is that its situation is obscured by lack of media attention toward this small, impoverished nation.

One LGBT organization that is doing its part to rise to the challenge of the UN’s appeal for relief is Rainbow World Fund, a San Francisco Bay Area nonprofit that seeks to raise public consciousness of the people’s plight in Niger. Jeffrey Cotter, executive director, explained, “Our own struggle with HIV/AIDS and civil rights has taught us of the power of visibility and coming together to help each other.”

RWF’s mission is to promote LGBT philanthropy for global relief and humanitarian service. In addition to helping people, the organization’s charitable efforts serve to build with other oppressed groups, to advocate for a greater global understanding of the LGBT community, and also to educate the LGBT community about world issues. RWF was in the news last December, after the devastating tsunami struck Indonesia, Thailand, and other countries. Several local fundraisers took place in an effort to raise funds for the stricken areas.

Now, Cotter is back with RWF’s latest effort. Though no formal benefits have been announced, RWF is seeking donations from the wider LGBT community to help those in Niger.

RWF’s cross-cultural reciprocity stems in part from the belief that in order to work against stereotypes about LGBT people it is important to illustrate the higher connection of people across the globe, and eliminate the patterns of oppression that affect not only queer people but other minority groups as well. The humanitarian goals of RWF are to eliminate oppression and suffering in all people, even if they do not sympathize with RWF as an organization. Using a sense of empathy and compassion, the people of RWF seek humanitarian causes in which they can make a significant positive impact, and create a cultural dialogue about LGBT issues.

Thomas Chupein, Niger relief campaign coordinator, illustrates this point, “In essence, by seeing our community as global and working to alleviate the suffering of others, we build bridges and harmony across cultures, and hopefully enlighten others to the common humanity of LGBT people.”

Building a world network of people who seek to end human suffering and promote peace is a lofty goal indeed. The LGBT community has sought this for its own people and RWF aims to use the lessons learned in this struggle to help people of the world.

For more information about Rainbow World Fund’s mission to help the people of Niger, or to make a donation, visit www.rainbowfund.org.

(2)

Sexuality and Gender Roles in Niger

http://lgbrpcv.org/category/countries-of-service/niger/

May 28, 2007

By Laura M. Bacon, Returned Peace Corps Volunteer Niger, 2002-2004

When I first met Amadou four months into my service in Niger, I felt unimaginable relief. Amadou was an enthusiastic, warm, generous Nigerien living in the rural village next to mine. He had a man’s name, a low voice, huge hands, facial hair, and was tall and built. Amadou also had painted nails, long braided hair, and wore high heels, make-up, and lots of jewelry. It was like a revelation meeting him. I had yet to find anyone in Niger, Peace Corps Volunteer (PCV) or Nigerien, who fit into the L, G, or B category. But now I had discovered a T. (trans person)

Amadou was the only Nigerien I ever met who did not fit firmly and solidly into an obvious gender category, and this came as a beautiful relief for me. I met him through my host mother, his distant relative. I often accompanied my mother on trips to Amadou’s place to purchase various herbs and spices. Amadou’s social circle consisted of a series of loosely-related, ostracized adults, ranging from childless women and effeminate men, to those with various disabilities and diseases.

I never experienced anything from Amadou’s mini-community but welcoming, friendly, and selfless engagement. Consistent with the hospitality and generosity ubiquitous in Niger, I was showered with gifts every time I visited Amadou and his housemates. Although we developed a friendship throughout my periodic visits to his household, Amadou warned me when he happened to be in my village that he should never be seen near my home or talking to me. He didn’t want to tarnish my reputation within my village by “outing” our friendship. Apparently his was already tarnished.

Having spent most of my college career in a very queer and queer-friendly community at Harvard, and hailing from the liberal state of Massachusetts (which legislated same-sex marriage while I served in Africa), joining the Peace Corps was a bit of a shock for me. Of our training group of 45, not one person was out. In fact, there were fellow trainees who uttered hetero-normative statements, occasionally made homophobic remarks, and expressed the view that (says the Bible) homosexuality is sinful. In those first months, I began longing for my community from home. I even dreamed during training of a magical training session led by queer-friendly rainbow-flag-waving PCVs!

Having spent most of my college career in a very queer and queer-friendly community at Harvard, and hailing from the liberal state of Massachusetts (which legislated same-sex marriage while I served in Africa), joining the Peace Corps was a bit of a shock for me. Of our training group of 45, not one person was out. In fact, there were fellow trainees who uttered hetero-normative statements, occasionally made homophobic remarks, and expressed the view that (says the Bible) homosexuality is sinful. In those first months, I began longing for my community from home. I even dreamed during training of a magical training session led by queer-friendly rainbow-flag-waving PCVs!

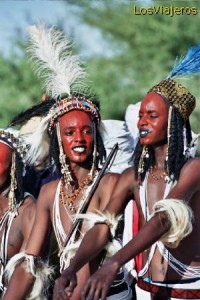

(photo: Woodaabe tribe members; credit state.gov)

Little by little things improved. I met PCVs with more seniority who were out or very queer-friendly. I even met one volunteer who was planning on beginning his post-service life in the States with his Nigerien boyfriend. And, when new training groups arrived, they included a more vocal and prominent queer contingency than my group.

Although my faith in the sexual diversity of the Peace Corps was restored, there were other aspects of my experience in Niger that left me feeling empty, lonely, and closeted in other, more substantial ways. What I missed most, while serving in Niger, was not so much being around gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and straight-supportive individuals. I missed witnessing love as I’d always known it, sharing my own romantic experiences from the past, expressing my sexual desires of the present, and being in the company of those who felt free to do the same. I especially missed a societal ability to blur gender lines and avoid assumptions and role expectations.

When we received our Peace Corps welcome packets, there was an entire section on “special types” of volunteers for whom Niger may pose difficulties. This included those with disabilities, vegetarians, women, and LGBT volunteers. We were all instructed that, as PCVs in Niger, there were many things we may have to get used to, suppress, or even hide because of cultural norms. This was fine with me. I had certainly gotten used to the idea of covering my head, shoulders and legs. And I knew I should not drink alcohol in this Muslim country.

However, I was unprepared to be barraged daily with:

-the belief that I, as a 25-year-old unmarried childless woman, was a pathos-inducing anomaly or, at the least, a curiosity;

-the practice of rigorously enforced gender roles, with women always seeming to emerge with less power and freedom; and

-the absence of the following within my rural village: dating, monogamy, fidelity, expressions of attraction, gestures of romance and flirtation, and even displays of love between spouses.

It is hard for me to describe the culture of Niger and how much it differs from that of the States. Our Peace Corps Director, when asked to describe Niger, often compared the culture of rural Nigerien life to that of biblical times. I’m not sure if his analogy was entirely apt, but he had a point. The food is similar: starches, sauces, and occasional meat.

Life trajectory is short, generally non-mobile, and filled with family and neighbors. Religion is devout; prayer almost constant. Work is hard, intensive and long. Marriages are usually arranged, and often viewed more as financial and familial unions than romantic manifestations. During my time in Niger we even experienced a plague of locusts, drought and famine, vividly recalling biblical stories.

My village was so different from what I was used to. I easily got used to eating millet with my hands, using the latrine, going without electricity and working in the fields. But I missed seeing women in power, girls in school, men and women working, praying, even talking together. I found it difficult that men wouldn’t shake my hand, wouldn’t look me in the eye. I resented the shame associated with sex and losing one’s virginity.

I was astounded that, because of this shame, women would never speak their husband’s name aloud, nor the names of their in-laws and first child. Women and men sat in different parts of cars, stood in different lines for the health clinic and held separate meetings and ceremonies.

The girls in my youth group told me that they wanted to wear pants as their group uniform so they could run and play and work more easily. But they came back the next day, disappointed to report that their parents would not allow this. Pants would be too much like prostitutes’ attire. These same girls were promised and married off as young as thirteen.

I cannot explain how liberating it felt to travel to the capital, or parts of Bénin, Ghana and Burkina Faso. There I got to see women on motorcycles, women-owned businesses, men and women holding hands, people openly speaking about boyfriends and girlfriends, young people going out on dates, choosing their partners. In my Niger community, while I certainly never witnessed romantic gestures, flirtation, or expressions of love between two people of the same sex, I must say I never witnessed these between a man and a woman, either.

I loved my time in Niger. My work was gratifying; the people in my village unforgettable. The country was exquisitely beautiful. My PCV friends were loyal and became lifelong. My entire extended service was wonderful. I feel deeply and profoundly grateful to the Nigeriens with whom I lived and worked, and to the Peace Corps for allowing me such a transformative and wonderful experience.

Yet I do not forget the isolation and frustration I sometimes felt during my service. Like Amadou, I often felt trapped in a body, a name, a role, and a culture that did not mesh well with my background or support my needs.

When I asked my host mother about Amadou (to determine which gender pronoun in Hausa was most appropriate, and to gain any insights on his/her gender bending), she answered in hushed tones that Amadou’s “manhood” had been lost. She said spirits had taken away his potency. Others whispered that too many drugs were the cause of his forsaken masculinity.

When I asked my host mother about Amadou (to determine which gender pronoun in Hausa was most appropriate, and to gain any insights on his/her gender bending), she answered in hushed tones that Amadou’s “manhood” had been lost. She said spirits had taken away his potency. Others whispered that too many drugs were the cause of his forsaken masculinity.

(photo: men bathing in Niger River; credit pbase.com)

Regardless of the reasons, I realized that Amadou’s dressing and performing as a woman was not a real choice. The binary sexual norms of his culture did not allow for a continuum of gender expression. Thus, societal pressures dictated that no matter who he really was – perhaps impotent, perhaps gay, perhaps transgender – he would feel and be treated as an outcast.

My host mother also mentioned that Amadou often became very sad, especially when no one was looking. Sometimes in the wider world, where (just like Niger) people become unwilling prisoners to societal expectations of gender and sexuality, I, too, become very sad.

You can contact Laura Bacon at lbacon@fas.harvard.edu