A week in sun-drenched Bali can be very seductive for anyone. Despite the bombings in ’02 and ’05, Bali continues to be a place of calm repose, swaying palms, restful beaches, green forests, friendly faces and master wood carvers. Bali is also home to a small resident lesbigay community that lives calmly among the easy-going mostly Hindu populace. Quite distinct from these locals are the international LBGT tourists who land in Bali for a short intense dose of beaches, beer and boys.

Also see:

Islam and Homosexuality

Gay Indonesia Stories

Gay Indonesia News & Reports 2004 to present

Gay Indonesia Photo Galleries

By Richard Ammon

Updated February 2008

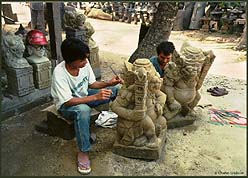

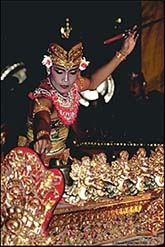

Come to Bali for the rolling surf, the white palm-lined beaches, the scarlet sunsets, the smiling Balinese charm, the informal beachfront cafes and economical holidays. Come for these and many other reasons such as the 100,000 temples, the brilliant colors of native costumes, the infinity of carved wooden furniture, puppets and plates and paintings.And come for the muted gay scene.

It only takes a couple of days to realize that Bali is more an ambient state of mind than a tangible vortex of queer culture; that Bali seduces a traveler with its orchids, incense and languid South Pacific pace–not it’s A-list of heated night haunts or political advocacy or even a LGBT community center. There are no gay organizations, no gay publications, no support groups, virtually no exclusively LGBT beaches, bars, discos or saunas.

Instead of small streets lined with go-go bars, massage parlors and cafes, as in Bangkok, Bali’s gay life is quieter and confined to a small handful of venues in the Semynak and Legian beach areas. There are several gay-friendly mixed bars and clubs patronized by mixed visitors and locals. Most show up after 11 PM looking for loud house music, disco lights, drinks, maybe drugs or food and perhaps a sweet-faced acquaintance willing to go further.

Even the most gay-identified bar, Q-bar in Legian, has its curious and straight customers who want trend and good sound. It also has a blend of rent-boys who may or may not be gay. There is a gay ‘spot’ on one of the beaches in Legian that some of the local residents have been trying to encourage as a gay beach. The afternoon I first visited, in 2002, there were exactly twelve guys—all friends—lounging around surrounded nearby by hundreds of non-gay locals splashing with their kids at the water’s edge, or doing tai chi or meditating into the sunset. Certainly no gay ‘scene’–yet. More recent news about this later.

Traditions

Although there are no specific laws that criminalize same-sex behavior in Bali, it’s not because of any enlightened government policies; rather, the lack is due to the blithe ignorance/indifference of legislators and authorities who have traditionally thought there is noting to legislate against. Same-sex behavior has certainly existed for ages within the Balinese culture, like any other culture, and was never considered a social threat or spiritual offense mostly because it was not spoken of or labeled.

In another story on this web site about Gay Indonesia

(Gay Indonesia) there is a description of male mentor-apprentice relationship (gemblok-warok) that has a long history in Indonesia. In the past this teacher-student arrangement was never questioned partly because it was not defined in sexual terms and many still resist modern simplistic cliches.

In Bali, it’s only been within the past generation that a ‘gay’ presence has been somewhat visible and audible, mostly due to the growing presence of countless lesbigay tourists (and TV shows) from Europe, Australia and America. Some of the local tolerance has certainly been motivated by financial profits (aka ‘the pink dollar’) as well as an inherent laissez-faire attitude of Balinese toward outsiders.

But Bali has not sprung to life as a gay mecca with festivals, flags or activists clamoring for equal rights. Instead, there is an informal ‘rural’ collection of friends energized by middle class western and Aussie expats who have moved their home and business to Bali for the laid back style, languorous ambiance, warm weather or the love of a fine looking Balinese man. These folks have created a resident casual community often with a western guy paired up with a native guy.

I made a slight random survey of three straight (I assume) young men about their thoughts on the matter. I asked them: if a friend of yours told you he was gay what would you think? A policeman said “he would still be my friend, but I tell him to go to temple to pray, to change that mind.” A Circle-K clerk said, to my surprise, that he did have a gay friend who performed drag in the Hulu bar sometimes. The clerk actually seemed rather cheerful and glad to tell me this. The third, a lifeguard, reacted with, “oh, not so good idea. But maybe not so bad. I think…but he have to get married.”

I made a slight random survey of three straight (I assume) young men about their thoughts on the matter. I asked them: if a friend of yours told you he was gay what would you think? A policeman said “he would still be my friend, but I tell him to go to temple to pray, to change that mind.” A Circle-K clerk said, to my surprise, that he did have a gay friend who performed drag in the Hulu bar sometimes. The clerk actually seemed rather cheerful and glad to tell me this. The third, a lifeguard, reacted with, “oh, not so good idea. But maybe not so bad. I think…but he have to get married.”

I told this to some expats and native Bali gays whom I met. They agreed that the youthful and open attitude of these local—all in their twenties–suggests a generational change as homosexuality becomes more of a vocabulary word, even if they don’t really understand the nature of it. But this is not to suggest that more tolerance translates to appreciation.

These straight guys as well as their gay peers are held in the tight grip of a tradition that can hardly be flaunted: marriage. It is a rare person, male or female, who can resist the insistent force from within one’s family and friend’s to take on a wife and make “new people” as a waiter at Q Bar told me one evening. At 21 he was living away from his small-village hometown in the north of Bali. He was clearly confused about his future; he didn’t want to marry but he thought he might have to. “Parents want my wife. I cannot be free,” he said bowing his head of silky black hair. “But I don’t think about that now.”

Hard Times at Ground Zero

Indeed he had more immediate concerns at the moment—making enough money daily to support himself. It was a major worry, when I visited in October 2002, for just about everyone on the island of Bali. The bombing of the Sari Club on October 12, 2002 (two weeks before I arrived) was catastrophic. Although life on the streets and beaches had returned to a normal pace, anyone associated directly or indirectly with tourism was still in a state of disbelief and worry.

Thousands of vacationers fled Bali within days of the explosion which also blasted out two other adjacent popular clubs. No one I spoke to failed to mention the frightening lack of tourists. Day or night, the alleys, arcades and avenues usually crowded with white-skinned foreigners in shorts, sandals and T-shirts were virtually empty. I wanted to buy clothes and souvenirs out of sympathy but that was impractical. So I ate out and left generous tips and didn’t bargain with taxi drivers even when I knew their rates were negotiable.

I visited the bomb site one sunny morning. Cordoned off with yellow tape, the scene looked like a scene from an apocalypse film. The usual bright colors of Bali were replaced by a black charred walls and white dusty collapsed floors and columns. A lot of the debris had been cleared from the area but there was still much broken glass, splintered wood and shattered cement pushed into piles.

Overhead, fragmented wires dangled on twisted telephone poles. Dark and rusting skeletons of cars and minivans still lined the street. Where the Sari Club once stood there only small mounds of ashen rubble being picked through by Australian forensic investigators in white coveralls. The building was completely gone. Next door and across the street were the burned out raw shells of the Aloha and Paddy’s clubs.

Former President Megawati, center |

As I watched the sight, I started chatting with a young policeman who spoke reasonably good English. We became more friendly and he told me that the President of Indonesia, Megawati (the daughter of former President Sukarno) was due to arrive shortly. With my 35mm camera and its zoom lens around my neck, which he admired, I let him assume I was a press photographer. When the police chief led the press onto the site’s center, a few feet from the eerie car-bomb crater, I went with them. As then-President Megawati arrived for a short visit (her second since the attack) we snapped our pictures of her surrounded by some security (surprisingly few) and local dignitaries who pointed out the progress of the cleanup.

Without any credentials and no press pass, I stood no more than thirty feet from her. I was taken aback at the lack of tight security. Had I intended harm to her, it would have been very easy. I couldn’t help wondering that if this was their best level of security how vulnerable Indonesia is to more damage. I had seen no search of the area (but how do you properly search a bomb site?) and although there were police and special military forces with semi-automatic weapons, their behavior was quite relaxed and casual. Even my policeman friend seemed more attentive to the local girls who stopped by for a look at the scene.

Fortunately Megawati’s visit went without incident at the site, although she was criticized politically in Jakarta for not taking a stronger hand in leading anti-terrorist action. Indonesia however, has given the impression that it is pursuing the killers by announcing the arrest of several suspects. (Megawati served two terms as President until 2005.)

Getting On, Fighting Back

But of course, life goes on. Among the modest gay community that lives full time in Bali, work was difficult. Rio Rabindra, owner of Bali Rainbow Leisure Travel (http://www.bali-rainbows.com/) who specializes in gay travel and tours in Bali, had a flurry of cancellations from abroad after the bombing, but did all he could to counter the ominous foreign government postings by making internet contact directly with LBGT travel agents abroad reassuring them that Bali did not pose any more of a threat than other international holiday destination.

Soon after, the southeast Asian members of ASEAN economic association meeting in Cambodia issued a strongly worded protest against the international travel warnings.

During my own visit Bali was as peaceful as ever in the southern tourist areas; not surprising since such random acts of terrorism rarely occur twice in the same place. It is generally acknowledged that the attack was not so much against Bali or Indonesia but more specifically against Australia (most of the night club victims were Australian) for its allied support of United States policies and actions in the Middle East and Western Asia.

One evening Rio and I sat down to dinner at Made’s (mah-day’s) Restaurant in Legian, a favorite with locals and knowing visitors. Half indoor-half outdoor under a warm moonlit sky the place was busy. (Well-seasoned international visitors appear to understand that modern life is full of possibilities as well as risks.) Rio ordered some nasi goring for me and another sort of goring for himself as he described the gay ‘scene’ in Bali. His conversation was generous and mixed with ideas about business, sexuality, social life and family.

“It’s only about ten years that we are more open and relaxed about this. You know here in Bali there is such a strong tradition to get married. We are easy about life here, but marriage has a strong fist here”, he said closing his hand. “But you know that doesn’t really change a person. So we have some friendly fathers here in Bali,” he said with a laugh.

Little is said about sexuality in families, let alone same-sex behavior. “Our culture is not ready for gay culture; people are afraid of it,” Rio observed. He and many of his gay friends manage to separate from their families by moving away to Denpasar, Bali’s only large city, with the truthful excuse of finding work.

A Modest Gay Scene

The public face of homosexuality here is more of a commercial business scene than a social community. In a few places such as Dejavu, Paparazzi, Q Bar, Liquid, Hulu Bar there is an easy mix of younger gay and straight people who frequent these places because these places have trendy styling and good music with an occasional drag show at Hulu.

Rio’s opinion was that such places misrepresented the real way of life in Bali. “You know we are quiet people. We don’t throw ourselves sexually at foreigners like in Bangkok. My tours are not sex tours. I don’t sell people…My friends meet for a drink or dinner or at the beach just for talking or volleyball. But the bars are too full of ‘sugar boys’ here from Java and foreigners with drugs. Some of the boys are straight and some are gay. I don’t like that but they are so poor I cannot hate them.”

A Spirit Named Angie

A second witness to Bali’s emergent gay life in recent years is a fey spirit named Angie—one of the best known gay guys in Bali. Working as public relations manager for Spy Bar, this charming character floated in to meet me for lunch at the beach side restaurant Madagascar by Legian beach. Looking somewhat feline with androgynous features and a calm self-confident poise, he was happy to talk about his life and Bali. What I assumed would be a quick hour interview stretched into three-plus hours as we chatted about the nature of life, human sexuality, multicultural families, personal identity, intimate relationships and more—interrupted several times by his greeting of friends and acquaintances who came by for a kiss or a sit under the broad banyan tree.

His conversation with me took no particular direction and I soon realized I would not be taking notes on this guy. He was genuinely himself and did not pronounce strong opinions or offer neatly tied observations about gay life in Bali. “I try to be true to myself. I am gay and if someone wants to accept that, fine. I don’t pretend to be anything else. I am good at what I do. I have re-made the public image of our scene and now it’s a very popular place.” Part of his work is to talk to customers who visit and make them welcome. “Even if they are here for a few days, I talk to them as a friend so they will remember us and come back or tell their friends.”

His conversation with me took no particular direction and I soon realized I would not be taking notes on this guy. He was genuinely himself and did not pronounce strong opinions or offer neatly tied observations about gay life in Bali. “I try to be true to myself. I am gay and if someone wants to accept that, fine. I don’t pretend to be anything else. I am good at what I do. I have re-made the public image of our scene and now it’s a very popular place.” Part of his work is to talk to customers who visit and make them welcome. “Even if they are here for a few days, I talk to them as a friend so they will remember us and come back or tell their friends.”

Angie’s circle of friends included gay and straight people. He didn’t see a difference: “We all want the same things in life, whether it’s with a man or a woman. The soul is bigger than sex and that is where I like to met people.”

Of Singaporean and Indonesian descent, he has lived in Europe and now feels perfectly at ease living his life in Bali. He makes no offense and accepts none in his daily affairs. He doesn’t think Bali should be any ‘gayer’ than it is. “You can’t impose these things on people. I think just being myself when I meet people and looking them in the eye in a kind way– they give me back freedom. Balinese will respect you if you respect yourself. I like it here”

|

|

On the Beach

Angie’s ease was also felt by others. He mentioned that he and some friends were making a small gay beach ‘scene’ in the Semynak area to talk, play volleyball and watch the sunsets. He invited me to meet some of them later that day. When I arrived there were a dozen men lounging by the sea and waiting for he sun to set. Could life be any easier than this, I thought. Rio was there with his Balinese partner as were several other couples, some mixed with one Balinese partner and the other from America, Europe or Australia.

By 2006 it was clear that Angie’s effort had paid off as revealed in this January 06 message:”I was at the Galigeo gay beach in Petitengent today and there were at least 100 guys there and as I write this, I am on the gay strip in Seminyak and it is full of gay people. I have been coming here for years as a gay tourist and have noticed a big change since the ’02 bombing. The ignorant ‘yoboes’ don’t come anymore but there are a lot more gays here.Spybar is no longer open but there are two great new bars called Dejavu and Paparazzi both right on the beach in Legian.”

As the sun turned to gold and then orange across the sea, I met Desmond from Australia and his younger Balinese partner Wayan. After a few minutes talking we discovered to our delight that we had mutual friends who lived in California. We talked about their business of purchasing Balinese goods for foreign buyers when they visited Bali. Needless to day things were slower since the bombing.

I was curious what effect their different cultures had on their relationship, so the next day we exchanged e-mail and this was Desmond’s reply which reveals some keen insight on the intricacies of living gay in Bali.

A Modern Gay Bali Couple

Desmond: “I had been living in Asia for 5 years or so by the time I met Wayan, plus I had been working in Asia frequently for 5 years before that. I already spoke the language and was somewhat aware of the cultural habits, restrictions, challenges that Wayan faced/dealt with before entering into a relationship with him. We were very pragmatic, discussing all of the obstacles, possible problems etc. before we entered into a serious relationship. This being his first, he needed some details on what to expect of a boyfriend, let alone a foreign one.

Painting by Symon |

“I realized that one day Wayan might be expected to be married, being the first son, he has a responsibility to support the family. It is not uncommon to hear that even after long relationships, Balinese men cave under pressure. I certainly hope this is not the case, and feel that, since his family know me, invite me (insist) to participate in ceremonies and refer to me as Wayan’s ‘Jodoh’ – partner – I am quietly confident that the unthinkable will never happen. If it does, may the first born be Wayan Desmond!

“I was already aware of the taboo of open displays of romantic affection, this is not unique to gays, but all Asians. Being gay is especially difficult; it is not uncommon to see two men caressing, holding hands, laying all over each other, these are the straight men! It would be inappropriate for a Bule (foreign guy) and a Balinese to be seen doing the same, particularly an older one with a younger one. But it would certainly be OK for me to hold hands with a mature, older man. Odd huh?

“The irony is that Wayan is very comfortable with open displays of affection when we are in Australia.

“Certainly, my introduction to Wayan and his family has brought enormous cultural, financial, materialistic, worldly changes for them. He was the first ever in his family to own a mobile phone, a motorbike, to travel in an airplane, to leave the country, own a passport, speak another language (other than Balinese and Indonesian), or see cable TV–how much more change can a family have experienced in 2 years? The path of his heritage has seen more change in two and a half years than it has in 200 years!

“I can never imagine how enormous the variances might be for him, (his culture and beliefs and mine) but he appears not to be bothered by them.

“Regarding the many spiritual beliefs and rituals here, I am sometimes ‘frustrated, annoyed, bored,’ with what I interpret as superstitious mumbo jumbo and ‘village mentality’ as it relates to things unknown or misunderstood. Wayan, however, is clever enough to see a different perspective and often states simply, ‘this is my culture’. Enough said as far as he is concerned—and so I stand corrected.

“Wayan’s straight friends are very formal because of their old culture/behavior toward colonialists. I have very little interaction with Wayan’s oldest friends (they are never that old). They regard me as one might when visiting an old school master–formal, polite, reverent. They have so little interaction with Bule’s (foreigners) that they are not comfortable around me. Of course they would not suspect that we are gay; it would never enter into their mind. I say, let’s wait until the last of them is not married–I hope it will be Wayan. Perhaps then they will understand.

“Wayan’s straight friends are very formal because of their old culture/behavior toward colonialists. I have very little interaction with Wayan’s oldest friends (they are never that old). They regard me as one might when visiting an old school master–formal, polite, reverent. They have so little interaction with Bule’s (foreigners) that they are not comfortable around me. Of course they would not suspect that we are gay; it would never enter into their mind. I say, let’s wait until the last of them is not married–I hope it will be Wayan. Perhaps then they will understand.

“My western friends from Bali have known Wayan for many years now, and relate to him as equal. Wayan’s English has improved 300% over the past two years and his ‘western wit’ takes many by surprise. Sadly, ‘locals’ are often regarded (by foreigners) as nice accessories. Wayan is not one of these. He might be silent on the outside, but there are bubbles of fury and passion beneath. As I have learned to become more Asian than the Asians, we have a very easy relationship in regards to cultural differences. Our age difference rarely proves to be a handicap; I am often the more infantile.”

Such are the words of gay folks who are weaving a mixed-cultural life with native traditions in this gentle island of Bali with the soft breezes and palm trees. I can recall only some of the words from the musical‘South Pacific’: “Bali Hai they call you, When the sky and the sea, And I don’t know how much what they’re saying, But come to me. Come to me.”

When you visit–or move to–Bali, you then begin to understand the meaning of the words and music much better.

Lifeguard Practice:Kutabeach

Lifeguard Practice:Kutabeach