A Place of Pilgrimage

If the curse of Shakespeare is having to study him in high school, the cure is a trip to Stratford on Avon, his vibrant birthplace in the heart of England’s historic Warwickshire midlands. A pilgrimage here is at least remedial, for many redemptive and, for the converted, no less than inspirational.

The cure started for me more than thirty years ago when I took c course in Shakespeare in a small Pennsylvania college. Thanks to a devoted literature professor, I discovered Stratford’s Shakespeare Institute. Four months and one ocean later I was listening to world class historians, scholars and literary critics during the day and spellbound by live performances at night in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre along the River Avon. I’ve been going back every year since–and staying with the same Stratford host family for three decades.

The cure started for me more than thirty years ago when I took c course in Shakespeare in a small Pennsylvania college. Thanks to a devoted literature professor, I discovered Stratford’s Shakespeare Institute. Four months and one ocean later I was listening to world class historians, scholars and literary critics during the day and spellbound by live performances at night in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre along the River Avon. I’ve been going back every year since–and staying with the same Stratford host family for three decades.

Historic Venues

Appearing like a movie set for Masterpiece Theatre, this ancient town absorbs the visitor and native alike in its old narrow streets. Students, actors, housekeepers, scholars, beer deliverymen, directors, school boys, visitors all move about, much as they have for centuries.

Appearing like a movie set for Masterpiece Theatre, this ancient town absorbs the visitor and native alike in its old narrow streets. Students, actors, housekeepers, scholars, beer deliverymen, directors, school boys, visitors all move about, much as they have for centuries.

Crooked half-timbered buildings with leaded glass windows lean out toward the narrow streets. A beautifully rickety King Edward VI Grammar School (Shakespeare’s childhood school) leans against the walls of the town’s oldest building, Guild Hall chapel, where, after five hundred years, schoolchildren still cram to learn the classics and the moderns.

Down on the lazy Avon River a bevy of swans glide past the Royal Shakespeare Theatre as actors rehearse yet another of the Bard’s scripts.

Not far away is the Hathaway Tea Room where afternoon high tea is served on mismatched tables that tilt with the sagging angle of the old wooden floors.

Not far away is the Hathaway Tea Room where afternoon high tea is served on mismatched tables that tilt with the sagging angle of the old wooden floors.

Fortunately for this town–and world history–Shakespeare was born here about April 23, 1564. He owned property here, retired here about 1610 and died here about April 23, 1616.

From his hand came about 37 plays, most written in London, some here, and a fair amount of poetry including 154 enigmatic and sophisticated sonnets. In the process, the Shakespeare family left numerous Elizabethan properties in tact that have been lovingly maintained by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, still with their 16th and 17th century appeal. I have walked through each of them touching and feeling the cracked wooden posts, weathered stone floors and smooth distorted glass windows of that distant age.

Each property exudes intense English culture and history. I almost expected Ann Hathaway (Shakespeare’s wife) to show up when I walked into her cozy thatched-roof house, ducking through its low doorways.

Shakespeare’s mother’s house (the Mary Arden house) stands half-timbered just outside town surrounded by period museums and summer gardens awash in color. The writer’s daughter Susanna (he had three children) married doctor John Hall and their house, Hall’s Croft, is my favorite Shakespeare property. It’s an impressive two-story example of the best of Elizabethan half-timbered town residences.

Trinity church just down the street from Hall’s Croft dates back seven hundred winters and is famous as the gravesite of Shakespeare. His name can be read in the church baptismal and burial documents on display. The inscription on his grave stone, near the altar, wards off any foolish notions with the engraved warning: “…and cursed be he that move these bones.”

The crowning piece of the various Shakespeare properties is his birthplace on Henley Street.

This has to be the literary counterpart of Bethlehem. The comparison is perhaps not unwarranted since it has been observed that more words have been written and published about the person and work of William Shakespeare than any other subject in the world except the Bible. (If you type ‘Hamlet’ into an Internet search engine, it will offer about 500,000 references!)

This has to be the literary counterpart of Bethlehem. The comparison is perhaps not unwarranted since it has been observed that more words have been written and published about the person and work of William Shakespeare than any other subject in the world except the Bible. (If you type ‘Hamlet’ into an Internet search engine, it will offer about 500,000 references!)

Royal Drama

But Shakespeare’s town is not just a picturesque post card of history, it is also the heart of a far greater domain: the Shakespeare ‘industry’ which reaches into almost every country and language around the world. There are countless theatrical play productions, academic lectures, scholarly research, books, university courses, and special seminars, not to mention the infinite variety of souvenirs and gifts fashioned on Shakespeare or derived from his dramatic ideas. Inevitably there are hundreds of local and international tours that are escorted through the famous venues and streets.

In Stratford, in addition to the historic town itself, which attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors yearly, the vortex of the industry is clearly is the Royal Shakespeare Company occupying the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. Here, along the banks of the gentle Avon, since 1879, the RSC has been performing an annual bouquet of Shakespearean drama that sets the standard for world drama.

In Stratford, in addition to the historic town itself, which attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors yearly, the vortex of the industry is clearly is the Royal Shakespeare Company occupying the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. Here, along the banks of the gentle Avon, since 1879, the RSC has been performing an annual bouquet of Shakespearean drama that sets the standard for world drama.

For the past hundred years, the bard’s plays have been produced here (along with other modern and classical playwrights) in a tradition that has received royal and professional blessings in the form of attending kings and queens. Prince Charles is the President of the Board of Governors and I saw him arriving one day for the annual meeting. Here too have come the greatest directors, designers and actors in the English speaking world, in both homage and for training: Olivier, Gielgud, Scofield, Redgrave, Burton, Richardson, Ashcroft, McKellan…

Academic Enterprises

In addition to the gift shops and performances, the industry also includes less visible but nevertheless impressive academic enterprises. The Shakespeare Institute, the Shakespeare Center and the RSC Educational Department manifest their educational work in the year-round stream of conferences, classes, books, theses, new editions, research, learned papers, university summers schools, high school courses, intellectual and critical lectures, teacher training seminars with actors and directors, exhibitions, and educational tours. The University of Birmingham has recently opened an enlarged 100,000-volume library here, shifting all its Elizabethan research materials from the main city campus in Birmingham to the more sylvan Stratford.

My alma mater, the Shakespeare Institute, still bustles with dons advising graduate students pursuing masters and doctorates in such specialties as textual criticism, performance history, Shakespeare’s life and Elizabethan literature. Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare’s contemporary and fellow playwright, is never far from the lips of these scholars. (Some still think he was the real author of the Shakespeare plays.)

My alma mater, the Shakespeare Institute, still bustles with dons advising graduate students pursuing masters and doctorates in such specialties as textual criticism, performance history, Shakespeare’s life and Elizabethan literature. Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare’s contemporary and fellow playwright, is never far from the lips of these scholars. (Some still think he was the real author of the Shakespeare plays.)

Shakespeare’s Secret

On a recent visit to Stratford I decided I would search for a knowledgeable answer to one question: Why is all of this here? How is it that one remote playwright who lived four hundred years ago could have achieved such secular sainthood and reverence as to be one of the most recognized figures in world history–and achieved that by yielding only a pen?

No artistic figure has ever gained the reputation and influence that Shakespeare has come to acquire over the centuries, and indeed he continues to acquire new respect and meaning for successive generations of inquiring minds. Surely there could be no better source to have my question answered than this half-timbered, hallowed and historic town.

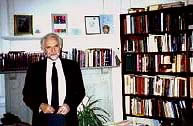

And few people are better positioned to answer my query than the authority I sought out in Stratford. Professor Stanley Wells is the former Director of the Shakespeare Institute and much respected Shakespearean scholar whom I first met thirty years ago.

And few people are better positioned to answer my query than the authority I sought out in Stratford. Professor Stanley Wells is the former Director of the Shakespeare Institute and much respected Shakespearean scholar whom I first met thirty years ago.

Surrounded by floor-to-ceiling books Professor Wells explained (probably for the thousandth time) several important reasons why Shakespeare is still such a powerful presence among us. First, “his works are plays and are therefore open to wide interpretation over and over. He was aware of their openness to performance and did not try to fix every character or action. He left ten percent deliberately available for others to fill in.”

Removing his reading glasses and letting his eyes wander around his wealthy pedagogical realm, he continued, “second, the literary quality of his writing is unmatched. He has influenced the language we speak; his vocabulary, his verse, his imagery has given us countless phrases we hear in common usage: “discretion is the better part of valour”; “to be or not to be, that is the question”; ” a coward dies a thousand deaths”, “parting is such sweet sorrow”…

Third, “Shakespeare’s thematic range is very great. It is remarkable that this mind could write an anguished Othello, a playfully silly Comedy of Errors, a deafening King Lear, a poignant Falstaff and a martyred Richard II. There is deep philosophy as well as emotional scenes of power and revenge or laughable love sickness;  there is fear of madness, jealousy and revenge, aging and grief. And of course, many different ways of death.”

there is fear of madness, jealousy and revenge, aging and grief. And of course, many different ways of death.”

Fourth: “and ultimately, because his works are entertainment; they were intended to be seen and acted in public. He wrote for the popular audience in his day, and because the plays are open to interpretation they are changeable, challenging and entertaining to perform and to observe.”

In the conclusion to one of his books, Wells further reiterates Shakespeare’s power and appeal: “he so often grapples with fundamental issues that never cease to concern us: with love and hate, with wit and folly, with the waywardness of the sexual instinct, with relations between generations, with violence and tenderness, with problems of self-government and of national government, with our need to come to grips with the inevitability of death and our yearning to find meaning in existence. He is finally the most humane of writers, the one who most poignantly convinces us of his compassion for his fellow human beings, and it is for this that we value him most.”

Such an elegy evokes the devotional as well as the intellectual passion that has sustained this Professor Wells for over forty years of learning and teaching. For just as each theatrical performance speaks Shakespeare with a different sound, so too each lecture, each essay, and each book speaks about Shakespeare with a new insight or a new interpretation. Even off the stage, Shakespeare is wonderfully elusive and alive.

World of Learning

Another golden treasure in the Shakespeare industry is the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust which is housed in the Shakespeare Center. The Center is home to two libraries and offers a vast array of educational programs for worldwide audience of students, teachers and scholars who come to Stratford every year.

The Trust was started in 1847 with the purchase of the Shakespeare birthplace house. In 1964 the Center was built next door to the birthplace in order to preserve the various Shakespeare properties and to centralize the burgeoning Shakespearean educational and tourist activities in Stratford.

The Trust was started in 1847 with the purchase of the Shakespeare birthplace house. In 1964 the Center was built next door to the birthplace in order to preserve the various Shakespeare properties and to centralize the burgeoning Shakespearean educational and tourist activities in Stratford.

I recall seeing the royal dignitaries cut the ribbon under a warm summer sun at the grand opening of the Center. It was also the 400th anniversary year of Shakespeare’s birth when the Royal Shakespeare Company performed all of Shakespeare’s history plays. I saw every of them, including three in one day!

The Center is very much a living and working school of art, full of life and learning. Students, teachers and scholars move through the halls daily to attend countless year-round lectures, seminars, exhibits and conferences that are offered by the Center, all overseen, at the time of this inquiry, by Dr. Robert Smallwood the deputy director.

Smallwood agreed with Professor Wells: “Why is Shakespeare so eternal? I think because in the end he is so unconfinable. He is infinitely varying for every generation as it reflects on itself. Here in Stratford, at the great RSC, they won’t get it right! They can’t get it right. That’s the wonderful mercurial genius of Shakespeare…Like Mozart, his works pull energy from the universe and deliver again and again.”

Smallwood agreed with Professor Wells: “Why is Shakespeare so eternal? I think because in the end he is so unconfinable. He is infinitely varying for every generation as it reflects on itself. Here in Stratford, at the great RSC, they won’t get it right! They can’t get it right. That’s the wonderful mercurial genius of Shakespeare…Like Mozart, his works pull energy from the universe and deliver again and again.”

Obviously pleased with his work and life in Stratford, he boasted: “There is a heritage here. The actors, the town, the scholars–there is a union of the artist with the academic that takes place here like no where I know of.”

Eternal Delight

That same night, with those two testimonies fresh in mind, I went to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre to see a production of ‘Taming of the Shrew’. Sitting there in the dark watching the action, the place, the rise and fall of Kate and Petruchio’s voices battling each other, seeing the color and use of costumes, lighting and stagework, it was as if I had never seen a play here before. The author’s drama was reborn before my eyes.

This moment of drama was now; it was fresh; it had never been never done before. The company might get it right–even if only for tonight.

It was another brilliant moment of Shakespearean action and language in the hands of inventive modern artists. The author would have approved because it worked to display new meaning for the thousand of us closely watching. Great Shakespearean drama does not fail in the hands of great artists–or great scholars.

It was another brilliant moment of Shakespearean action and language in the hands of inventive modern artists. The author would have approved because it worked to display new meaning for the thousand of us closely watching. Great Shakespearean drama does not fail in the hands of great artists–or great scholars.

And so the world is blessed by the town known as Stratford and the ‘industry’ known as Shakespeare. My journey to Stratford on Avon had been redemptive and evocative. Cured again.

P.S. In case you didn’t know:

From: The Australian, Australia (http://www.theaustralian.com.au/ ) http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/common/story_page/0,5744,6320234%5E1695 3,00.html

22 April 2003

Shakespeare’s sexuality in doubt

By The Times

Ian McKellen has reignited the debate over Shakespeare’s sexuality.

McKellen, 63, a highly respected actor and key figure in the gay rights community, says he is convinced Shakespeare was homosexual because of his depiction of gay relationships. “Did he sleep with another man? I would say yes.”

An examination of his plays makes it clear, McKellen says, that Shakespeare had a close understanding of gay relationships. “Look to where it matters: his work, where Shakespeare certainly writes about gay people. “One part which I want to play is Antonio in The Merchant of Venice. His first line is: ‘In sooth, I know not why I am so sad.’ The audience knows that it’s because his boyfriend has come to him to borrow money to get married.”

McKellen says the play is built around the love triangle between an older man, a younger man and a woman. “The Merchant of Venice centres on how the world treats gay people as well as Jews.”

Shakespearean expert Anne Barton, a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, disagrees. “Ian is barking up the wrong tree on this,” she says. “I don’t think for an instant that Shakespeare slept with a young man. You won’t find an academic consensus that Shakespeare was gay.”

The discovery last year of a portrait of Shakespeare’s patron, the third Earl of Southampton, apparently dressed as a woman, reinvigorated the argument that the pair had a sexual relationship. But Barton says that Shakespeare’s Sonnet XX, believed to have been written to the earl, indicated that their relationship was cerebral rather than sexual. The poem concludes: “But since she [Nature] prick’d thee out for women’s pleasure,/Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.”

Shakespeare’s exploration of the relationship between Antonio and Bassanio in The Merchant of Venice is important, but it is significant that Antonio is left on his own at the end, Barton says. “When the couples go off at the end, there’s no place for a threesome. Antonio has to shrug his shoulders.”

McKellen admits the evidence for Shakespeare’s sexuality is circumstantial, but says the immense complexity of sexuality in the Bard’s comedies confirms his belief. “We really don’t know for sure if Shakespeare was gay and it is not especially important. But was he interested in sexuality? Absolutely. Did he know about it? Better than anybody.”

Another Shakespearean scholar, Diane Purkiss of Oxford University, says inferring Shakespeare’s sexuality from his characters in The Merchant of Venice is like inferring that he was Jewish. “What we do know about Shakespeare’s life indicates that he was heterosexual.” “It is true that there was a culture of being attracted to young boys in 1690s London,” she says. “But it is very difficult to know whether he was part of it.”

Shakespeare’s homoerotic poetry does not necessarily indicate that he was homosexual, she argues. “We know that there was a culture of writing homoerotic poetry at the time.” McKellen acknowledges that Shakespeare was married to Anne Hathaway and had three children by her, but says the playwright’s decision to leave her to live in London showed his lack of interest in her. “He was living very far away from his wife,” the actor says. “What does that tell you?”

Also see:

England Stories

England News & Reports 2000 to present

England Photo Gallery